Story

Ms. L was referred to DiCarrado Physical Therapy in November of 2021 by her previous physical therapist. The referring physical therapist felt the patient would be better off with outpatient based home physical therapy performed by a PT with experience in complex neuro/ortho cases. Ms. L was first assessed on November 16, 2021 and reassessed using an ISM focused evaluation on December 11, 2023.

Ms. L is a 25-year-old college student in NYC who presented to her initial evaluation in 2021 with complaints of “neck pain, painful popping in the throat, chronic daily joint subluxations and dislocations, movement and painful spasms in the throat causing loss of vision and significant difficulty breathing occurring for the past 2-3 months, general difficulty breathing through limited rib cage expansion, swallowing and problems with cognition and difficulty speaking.” Around age 16, Ms. L was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) type 3 hypermobility, Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), Mast Cell Activation Syndrome, and cervical instability.

- Diane’s question:

Over time, an experienced clinician develops hypotheses in relationship to patterns of symptoms; however, there are some new ones in this story for me!! The one I’m curious about is your thoughts on ‘movement and painful spasms in the throat causing loss of vision’. Now I assume the word ‘causing’ is her word, not yours given this is in quotation marks. By what biological mechanism do you think movement/spasms in the throat can cause loss of vision?

- Stefanie’s response:

I believe there are several possible mechanisms. She seems to be describing symptoms similar to a pre-syncope event. She does have clinical cervical instability and was considered for spinal fusion surgery but wanted to finish college first. These neck spasms are likely related to excessive movement in her upper cervical spine and are her nervous system’s attempt to stabilize her upper cervical segments. The spasms and/or the excessive motion can compress the vertebral artery and create a decrease in blood flow to the brain. This compression either deprives the optic nerve of blood flow causing that vision loss or simply kicks off a syncope event (she will report “losing time” but she remains sitting so it does not appear that she actually faints). Another possible mechanism is irritation/facilitation/slight compression of the vagus nerve causing dysfunction within the polyvagal circuitry. This is an area that has generated a lot of interest for me recently. Vagal nerve compression could initiate a vasovagal type response leading to the pre-syncope symptoms and/or there could be a disruption of the occulocardiac reflex mediated by the vagus nerve.

- Diane’s comment:

All biologically plausible mechanisms. The optic nerve is supplied by branches of the ophthalmic artery which is derived from the carotid, so compression of the vertebral artery wouldn’t impede this flow; however, the occipital lobe itself is supplied by the posterior cerebral artery which branches from the basilar which is derived from the left and right vertebral, so this may be another mechanism for visual disturbances, especially if the disturbance is not one entire eye but rather ½ of each eye?

Her plan was to “survive” college and have cervical fusion to correct her cervical instability after graduation however, due to her symptoms she was considering leaving college and moving back home. After 2 years of in-home outpatient physical therapy, including the use of ISM principles with moderate symptom improvement, Ms. L was no longer having episodes of throat spasms that dangerously impaired her ability to breath and that would cause her to pass out. Her painful throat popping had reduced, her grey outs and partial losses of consciousness reduced in frequency, and she felt she could continue with her studies. She also reported feeling more aware of her body position and improved ability to stop grey outs by correcting her cervical segments manually. Her daily subluxations, vision difficulty, air hunger/lack of rib cage expansion, poor posture, pain/dysesthesias in the face and decreased bodily awareness continued but with reduced frequency. She continued to have episodes of gagging, vomiting/dry heaving (she felt these episodes were more autonomic in nature rather than due to something she ate) and often experienced a lack of hunger signals. It should as well be noted that during the non ISM initial evaluation, patient demonstrated impaired cranial nerve function: decreased facial sensation on the left (CN V), cervical spasms when saying “ahh” with uvula deviation to the right (CN IX & X), asymmetrical facial expressions – most specifically uneven smile with less activation on the left (CN VII), and tongue deviation to the right (CN XII).

Ms. L’s EDS, POTS and Mast Cell Activation were, and continue to be, treated and monitored by several doctors. She has had cervical imaging to document her cervical instability at C1 and C2 with her EDS specialist who wanted to monitor her for changes but did not recommend cervical fusion surgery just yet. Ms. L was, and is, very aware of her anatomy and the workings of the nervous system and often reports symptoms using anatomical terms.

Ms. L lived in an elevator building with her girlfriend and service dog, used a power wheelchair for community mobility and 1-2 loftstrand crutches for household mobility. She had a Home Health Aide (HHA) that came in for a few hours each day to assist with activities of daily living (ADL) and household chores. She has since graduated college and moved to Hawaii to start her post collegiate life.

Meaningful Complaint

At the time of the ISM focused assessment in December 2023, patient reported a scary incident that occurred when she turned her head to the left. She experienced a major spasm in her throat area that shifted and rotated her trachea to the left. She felt a sharp pain in her throat and felt her pulse increase and began to lose vision in her left eye.

- Diane’s question:

What muscle can rotate the trachea to the left? How does this cause loss of vision in the left eye?

- Stefanie’s response:

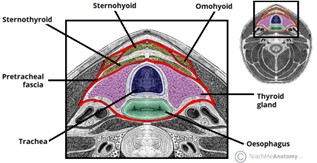

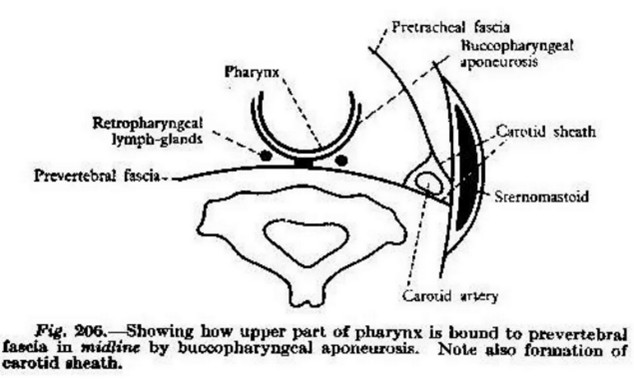

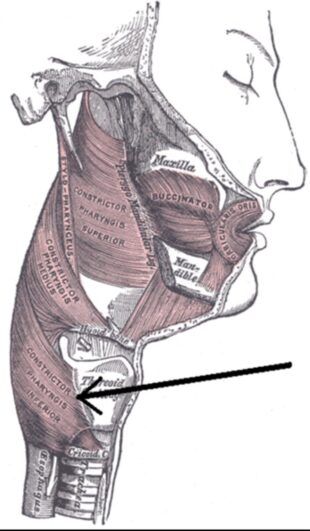

This was something that really fascinated me as well – we have the spasm, pain, an increase in pulse, and vision loss. My first thought was something triggered the autonomic nervous system via irritation/facilitation/slight compression of the vagus nerve. This could be due to the spasm itself or to the cause of the spasm which is likely her cervical instability. The muscle that is rotating her trachea is tricky. She is subjectively reporting that her trachea feels like it is rotating in these moments, but she often places her hand on her cricoid cartilage. The few times I was able to witness this happening, it appeared to shift to the left more so than rotate. With passive correction and vector analysis of the cricoid cartilage/trachea, I felt a resistance pulling to the left and very slightly upward. Based on that, the main muscle I suspected was the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle since there are insertions into the cricoid cartilage and has an orientation that would pull up and back. Interestingly enough, this muscle is innervated by branches from the both the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves. However, this pull may also be related to buccopharyngeal fascia (BP) restrictions as both the trachea and esophagus are enveloped by a continuation of this fascia.

- Diane’s comment:

The buccopharyngeal fascia attaches superiorly to the medial aspect of the medial pterygoid plate, so one way to differentiate the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle from the BP fascia would be to palpate the greater wings of the sphenoid and have her breathe in. If the tension was in the BP fascia you would feel the greater wing of the sphenoid be pulled inferiorly on the inhale breath.

She was able to relax the spasm by pulling and rotating her trachea to the right and C1 / C2 to the left (as instructed in previous PT sessions).

- Diane’s question:

I’m sure you will get into all this later in the report; however, for clarity here, and my understanding, were both C1 and C2 rotated to the right? In other words, the OA joint was left rotated, AA neutral and C2-3 rotated/sideflexed right? Or some other pattern?

- Stefanie’s response:

This patient’s presentation would vary; sometimes it was as you described with the OA joint left rotated and AA joint neutral with C2-3 rotated/sideflexed right. However, other times it was OA neutral, AA joint left rotated, and C-2 neutral so the patient was instructed to put her fingers in the area of C1/2 and rotate them to the left while rotating the trachea to the right as a less specific self-correction that would work to prevent vision loss/grey outs.

Additionally, she reported minimal to no hunger signals, achiness in bilateral cheekbones and a deep tension pull on the crown of her head along with jaw issues, specifically a feeling of her bottom teeth pushing forward on her top teeth. The comparable sign during the assessment was the gagging sensation she felt when she sitting with her trunk, head, and upper extremities unsupported.

- Diane’s comment:

We are going to get into her cranium for sure with these symptoms!!

Cognitive and or Emotional Beliefs

Ms. L has lived with her diagnoses and varying levels of symptom severity for 10 years. She has developed a pragmatic and at times detached way of speaking about and regarding her body. She often reports symptoms by prefacing with comments such as “this is how it feels, but I know that’s not what is actually physically happening.” Due to her chronic pain, she has learned to detach from her body and ignore painful areas; she has implemented strategies to help desensitize her overactive nervous system such as exposing herself to loud noises that used to cause great discomfort.

Meaningful Task

Since Ms. L was a student and a powerchair user, sitting unsupported was selected as the meaningful task (MT) since that is something she must do to take notes in class, complete her assignments and perform ADL. Sitting unsupported is a challenging task that often brings on feelings of air hunger and gagging. Due to the complex nature of Ms. L’s condition, sitting unsupported will be the starting screen and the screening task.

- Diane’s question:

Air hunger is often a symptom of hypocapnia, or over breathing in excess of metabolic demands. What other mechanisms do you think of when someone complains of ‘air hunger’ and how would you differentiate them from hypocapnia?

- Stefanie’s response:

My immediate thought with this patient, when considering all her symptoms, is that the air hunger has to do with limited expansion of her diaphragm due to the buccopharyngeal fascial restrictions as well as likely vagal nerve dysfunction. Some symptoms of hypocapnia include painful paresthesia and numbness in hands and feet which this patient did not report. In acute hypocapnia people can present with rapid breathing and tachycardia but since this is more of a chronic report for this patient, that presentation would not be expected. For Ms. L, I first investigated if any correction I made restored her breathing and eliminated the feeling of air hunger. If I had not found any, then I could have checked for positive Trousseau and Chvostek signs that could indicate a hypocapnia induced reduction of calcium blood levels and if needed, recommended arterial blood gas (ABG) test to check pH and CO2 levels within the blood. Trousseau’s sign occurs if the MCP joints and wrist spasms into flexion when a blood pressure cuff is inflated on the upper arm and cuts off blood supply. Chvostek sign occurs if muscles of the face, typically around the mouth twitch when tapping the facial nerve anterior to the ear. Thankfully, corrections I made involving the cranial, cervical, and thoracic regions helped reduce her symptoms.

Screening Tasks

Ms. L has a complex system. As a result of her medical diagnoses and physical disabilities, a task that requires repetitive motion could create two problematic scenarios. One possible scenario is that the repetition of the task creates an autonomic reaction or spasms that compromise the position of her cervical spine resulting in a loss of consciousness, difficulty breathing, and/or vomiting/gagging. A second problematic situation from repetitive movement could be simply that to complete the task Ms. L moves differently and her system reacts differently so that findings are not consistent. For these two reasons, sitting unsupported was the only position assessed for all functional units as both the starting screen and the screening task. However, to note the position of the sacrum in sitting, the patient’s sacroiliac joint (SIJ) was additionally evaluated going into a mini-squat.

Mini-Squat

The optimal mechanics of sitting down from a standing position requires the SIJ to remain locked so that a person will sit on a stable pelvis. If a patient sits on an unstable pelvis, the patient may compensate in other regions leading to pain and dysfunction. The SIJ is not evaluated once seated so this must occur prior to sitting. A mini-squat was all that was needed to detect an unlocking pelvis.

- Diane’s question:

The term ‘locked’ may not be familiar to all readers. Can you describe what you mean by the term ‘locked’. What is the relative position of the sacrum to the innominate when the SIJ is locked vs unlocked? Tell us the impact on the form closure mechanism (ligaments of the SIJ) in both positions.

- Stefanie’s response:

A relative position of slight (not full) sacral nutation, with the sacral base being rotated slightly more anterior relative to the innominates, would be considered a “locked” SI joint and is considered optimal when the joint is in a weightbearing position such as standing or sitting. This relatively anterior position (nutated) of the sacrum to the innominates creates tension in the sacrospinous, sacrotuberous and posterior interosseous ligaments. Along with the anterior and inferior translations of the sacral articular surfaces, the ligamentous tension creates the form closure necessary to help control shear and rotational forces during light load transfer. An unlocked SIJ would be the exact opposite. It would mean a more posterior rotated position (counter-nutated) of at least one side of the sacrum relative to the adjacent innominate. The posterior and superior translation of the sacral articular surface(s) would slacken the sacrospinous, sacrotuberous, and posterior interosseous ligaments while tightening the long dorsal ligament resulting in a more loose packed position of the SIJ with decompression occurring between the joint surfaces.

When Ms. L performed a mini-squat, both SIJs unlocked. This indicated the need for manual compression of the pelvis as Ms. L sits down or having her perform a seated self-administered technique often referred to as “clearing one’s sits bones” in which she would shift weight off one innominate and pull her gluteal tissue near her ischial tuberosity (IT) laterally and then repeat on the other side.

Ms. L would often shift her body around once seated negating the impact of pelvic compression during the task of a stand to sit transfer and so clearing her sits bones was the chosen method of ensuring she was always seated on a stable pelvis for her sitting unsupported assessment.

- Diane’s question:

How does manual compression of the pelvis result in ‘locked’, or stable, SIJs? How does the task you ask her to do when seated result in a ‘locked’, stable pelvis?

- Stefanie’s response:

Manual compression, in addition to a correction of the TPR, mimics the action of the deep lumbosacral fibers of the multifidus that would compress posteriorly and medially across the SI joint surfaces. It would ensure no excessive movement of the sacral base occurs either unilaterally or bilaterally into a position more posterior than the innominate joint surface. The very anatomy of the sacral segments with different orientations , irregular bony surfaces, and irregular cartilage on the ilium allows for them to prevent shear when the joint is compressed.

The theory behind this self-administered technique is that the pulling the soft tissue away from the ITs will increase awareness of body alignment over the pelvis and allow the patient consciously or even subconsciously to center themselves over the pelvis and allow the natural locking mechanism to occur at the SIJ.

- Diane’s comment:

I would suggest that if someone was over-activating their levator ani muscles, merely pulling the soft tissue of the gluts laterally may not cause the sacrum to ‘self-lock’. My preference is to have the client actually grab the medial side of the IT and pull it lateral and then pull the entire pelvis into an anterior tilt by directing the pull on the IT posteriorly. It only matters that you can ensure the SIJs are self-locked, there are likely a few ways to achieve this!

Sitting Unsupported

Assessing the ability of a person to sit unsupported allows for evaluation of a task that is an integral component of a wheelchair user’s ADL and student life. Pain or discomfort experienced during sitting can impact the ability to perform other tasks requiring use of the upper extremities and/or the head / neck. For a person with compromised mobility of the lower extremities, unsupported sitting is an appropriate and important screening task.

Optimal sitting unsupported posture would include a neutral, and stable, pelvis and spine without excessive frontal, sagittal, or transverse plane rotations in the lumbar, thoracic or cervical spine. Specifically, the thorax should not have any rotated/translated rings, the cervical spine should not have any translated segments, and the cranium should remain in neutral.

Functional Unit #1 (FU#1)

- Pelvis: Left transverse plane rotation (TPR), posterior pelvic tilt (PPT), left iliac crest higher than right indicating a lateral tilt, bilateral unlocked SIJs

- Diane’s question:

When the pelvis is rotated in the transverse plane to the left, it is often associated with a left intrapelvic torsion (IPT). What is the difference in relative position of the sacrum to its innominate between an unlocked SIJ and an IPT?

- Stefanie’s response:

The sacrum should always be in a nutated position relative to the innominates for optimal load transfer. When the pelvis is rotated in the transverse plane, one side of the sacrum should nutate slightly more allowing the sacrum to rotate in the same direction as the pelvis. If an SIJ is unlocked, that tells us the sacrum is not rotating in the same direction as the pelvis or at the very least it is not rotating as much as it should be to maintain optimal alignment with the innominate. In a L TRP with a L IPT – the pelvis is rotated to the left in the transverse plane and so the sacrum would also be rotated to the left (and slightly more nutated on the R as relative to the R innominate).

- Diane’s comment:

The left side of the sacrum should also be nutated relative to the left innominate. Because the left innominate is posteriorly rotated relative to the right innominate it rotates the sacrum to the left so it ‘appears’ like the sacrum is less nutated on the left. However, since the innominate has posteriorly rotated on the left, I think the amount of nutation on both sides can be close to the same amount. Regardless, you are right – both sides of the sacrum are nutated relative to their respective innominates.

- Hip: Right head of femur (HOF) more anterior to left (congruent to the TPR of the pelvis), unable to check right HOF in relation to the right acetabulum

- Thorax: The entire thorax was noted as compressed with the lower thorax rotated to the right and the middle thorax rotated to the left. The 7th and 9th thoracic rings were found to be rotated to the right with the 8th thoracic ring rotated to the left. The alignment of the 7th and 9th thoracic rings were incongruent to the position of the pelvis (L TPR) and right hip. The 6th and 5th thoracic rings were rotated to the left and are incongruent with the position of the 7th and 9th thoracic rings. The 4th thoracic ring was rotated to the right. Rings 5 and 6 are likely causing the rotation of the mid thorax to the left.

- Diane’s comment:

You are correct – this is a highly compressed thorax with one regional ‘sandwich’ or rings rotating in alternate directions (TR7,8,9) and 3 other rings not stacked (TR4,5,6). No one ring correction is going to change this!

To further evaluate the thoracic region, the patient was cued into autogenerated spinal traction to her best ability with manual guidance and support from the therapist to achieve a more elongated seated posture – normally a posture she is unable to maintain for longer than 5-10s and a posture that typically creates cervical flexion and often cervical left sidebending.

- Diane’s question:

Are you saying that when Ms. L elongated her thorax her neck flexed and left sidebent or are you saying that this is a common finding? Please clarify if this did happen for Ms. L and even it did not, what is your hypothesis as to why lengthening of the thorax would create shortening of the neck, and how would this potentially change the direction of your assessment?

- Stefanie’s response:

When asked to “sit up straight” for autoelgonation prior to this evaluation, cervical flexion always occurred and a left cervical sidebend sometimes occurred. In this particular instance, both cervical flexion and a left cervical sidebend occurred.

- Diane’s further question:

What is your hypothesis (that you have already suggested in her story) as to what could be caused the flexion/sideflexion of the head and neck to occur when she elongates her thorax and how would you test this hypothesis? Did you happen to notice any change in the horizontal level of her eyes (not relative to the neck but intra-cranially)?

- Stefanie’s response:

My hypothesis was related to the buccopharyngeal fascia, that when she elongated her thorax, the esophagus (enveloped by a continuation of the buccopharyngeal fascia) elongated and pulled on the buccopharyngeal fascia. The fascia forced the left cervical sidebend and cervical flexion may have occurred for the same reason but I felt it had more to do with its position in the retropharyngeal space. If it was purely a left buccopharyngeal restriction, then I think only a left sidebend would occur. Since there was cervical flexion with a bias toward the left, I think both sides have a restriction in the cervical spine, but the left side also has a restriction that goes up toward the sphenoid. During this specific session, I do not believe I noticed any change in the level of her eyes, but in subsequent sessions I did notice a worsening of the left sidebend of the sphenoid when correcting her thoracic rings.

This auto-elongated posture revealed right rotation of rings 4 and 7 with the 4th ring being the most rotated and left rotation of rings 5 and 6 with the 6th ring being the most left rotated. To summarize, the rotation of ring 7 is incongruent with the pelvis with rings 5 & 6 being incongruent with ring 7 and ring 4 being incongruent with 5 and 6. These findings were further supported in a later session when patient could tolerate a moderate antigravity position in quadruped propped on elbows so that her shoulders were lower than her hips.

- Diane’s question:

To be clear, was the change from the sitting unsupported position to the sitting auto-elongated position of the rings, the following:

TR 8 & 9 stacked in the elongated position TR7 remained right rotated (a single ring impairment)

TR5 & 6 remained left rotated, TR4 remained right rotated (a 3 ring impairment)

- Stefanie’s response:

Yes, that is exactly what the elongated posture revealed

- Lumbar: L5 was noted to be left rotated (congruent with the L TPR of the pelvis), with L3 in neutral and L1 and 2 right rotated (incongruent with L5, but congruent with the lower thorax)

FU #1Driver(s)

Manual correction of TR4,5,6 & 7 could only partially be achieved with a very strong vector that seemed to pull from inside the rib cage. Correction of TR7 within its available range did not impact the positions of TR4,5,6. Co-correction of TR 4,5,6 within their available ranges corrected TR7 to its fullest extent (but remained only partially corrected). Correction of just TR4 worsened TR5&6 and correction of just TR5&6 worsened TR4.

Co-correction of TR4,5,6 within their available ranges yielded complete correction of the pelvis, R hip, and lumbar spine.

- Diane’s question:

To be clear, correcting the alignment of TR4,5,6 restored full control of both SIJs in the squat to sit task and the LTPR. If the pelvis corrected, it makes total sense why the right hip and lumbar spine corrected. Why?

- Stefanie’s response:

The lumbar spine and hip were congruent with the pelvic TPR and likely being pulled along with the pelvis as it rotated. Anything correcting the pelvis would correct the hip and lumbar spine as well. I was not able to manually check the SIJ while manually correcting the rings but the improvement in the pelvis, lumbar, hip position, overall thoracic position and subjective experience lead me to believe there was a restoration of SIJ control.

Subjectively, the patient felt the best with the co-correction of TR4,5,6; however, her head/neck (HN) was observed to sidebend to the right although the patient was not aware of that. Unwinding the rotation of the pelvis, neutralizing the PPT and the lateral tilt while adding SIJ compression resulted in a worsening of the gagging sensation and a feeling of tightness in the neck, and created a right sidebend in the mid thoracic region.

- Diane’s question:

Any ideas yet what structure lies “inside the thorax” and becomes the pretracheal/buccopharyngeal fascia in the neck?

- Stefanie’s response:

The primary driver for FU#1 was therefore determined to be the thorax with TR4 (RR) and TR 5&6(LR) as the priority rings with TR4 glued to TR5&6 and TR5&6 appearing compressed. TR6 was left rotated to a greater extent than TR5.

Only partial corrections were possible for these three rings which indicated the need for an articular assessment, but during the correction, a very strong long vector was noted from within the thorax itself.

- Diane’s question:

There is another impairment/vector that I am thinking about here that could result in worsening of the head/neck when the thorax is corrected and it’s not the articular system. Any idea?

- Stefanie’s response:

The main impairment/vector that jumps out at me is the buccopharyngeal fascia and/or a neural vector having to do with the vagus nerve.

- Diane’s comment:

YES YES YES!!! Think of a vector from the pericardium/pretracheal/buccopharyngeal fascia like the dural system impairment. No MSK driver can be found since every regional correction makes something else worse. This vector has to be treated first, even before any articular assessment. You don’t have a MSK driver here since correcting the thorax worsened the neck and head.

Functional Unit #2 (FU#2) Findings

Further compression was noted in FU#2 with incongruent rotations between the thorax through to the cranial regions. The findings below were found during unsupported sitting.

Cranial: Cranium was held in a left ICT with incongruent right rotated and left sidebent sphenoid

- Diane’s comment:

Here is your evidence that the buccopharyngeal fascia is involved – it is what commonly sidebends the sphenoid and creates the vector that behaves much like the dural system impairment limiting auto-elongation of the thorax without compromising the neck/cranium.

- Cervical: Left rotated C2 (congruent with the L ICT, specifically the L rotated occiput with C7 incongruent in right rotation.

- Shoulder girdle: The shoulder girdle and manubrium were right rotated with the left clavicle anteriorly rotated and the right clavicle posteriorly rotated which was congruent with C7 and incongruent with TR1

- Thorax: TR 1 left rotated and TR 2 right rotated. TR2 was congruent to TR4 from FU#1.

In the auto-elongated position described in FU#1, the cranium remained in a left ICT, C2 remained left rotated, C7 and the shoulder girdle remained right rotated, but TR1&2 correct.

FU #2 Drivers(s)

- Diane’s question:

To understand the findings below, were they done in the auto-elongated position (a correction as well) in which TR1 & 2 correction occurred, or her habitual sitting position?

- Stefanie’s response:

These were done in her habitual sitting position.

Manual correction of the cranium involved unwinding the ICT with concurrent left rotation and right sidebending of the sphenoid. This correction reduced the gagging sensation and restored control to the cervical region allowing the patient to elongate her neck and hold a more neutral position.

- Diane’s question:

Did correcting the cranium restore C2 and C7 alignment? You note that the patient was able to elongate her neck and hold a more neutral position so I suspect something more than control happened to the cervical segments.

- Stefanie’s response:

C2 and C7 were partially, but not fully corrected, by correcting the cranium. I was able to palpate C2 while correcting the ICT with both hands but to palpate C7, I had to use one hand to correct the cranium, so I question my effectiveness. C2 was mostly corrected but not fully corrected when correcting the cranium. I also used her ability to elongate her neck and hold a more neutral position as evidence that there was an improvement in alignment of the cervical segments. Ms. L was unable to move her arms up to her neck to monitor these segments herself.

No observable change was noted in the shoulder girdle and patient did not feel any change in TR1 or 2 (patient was instructed on where to put her hands to feel movement in those rings).

Manual correction of C2 alone worsened C7 and TR1&2, but partially corrected the shoulder girdle. Using a mirror, no observable change in the rotation of the cranium or sphenoid was noted with C2 correction alone. C7 correction alone worsened C2, partially corrected the shoulder girdle, fully corrected TR1& 2 but had no observable impact on the cranium or sphenoid. Co-correction of C2 and C7 fully corrected the shoulder girdle, TR 1&2, but did not have an observable impact on cranium or sphenoid. Co-correction of C2 and 7 provided Ms. L with the best subjective experience in her cranial and cervical regions, but reported a slight pain around TR6 on the right and a pull both into the right side of her face and down into the diaphragm.

- Diane’s question:

Did the co-correction of C2 and C7 change the gagging sensation as well as the co-correction of the sphenoid and ICT? Where do you think the pull down into the diaphragm is coming from with this correction? Hint: the sidebent sphenoid is also likely being impacted by this vector of force and one of the reasons why I would choose the cranial region as the primary driver here.

- Stefanie’s response:

Yes, my apologies for not specifically stating that – C2 and C7 co-correction resulted in the best subjective experience which included the resolution of the gagging sensation and even air hunger as well. The buccopharyngeal fascia is the vector to which I believe you are referring. I was always bouncing between a cranial or cervical primary driver for this patient. She certainly appears as a cranial driver, but I found if I started with the cranium, the releases would take a lot longer and at times would cause discomfort in the cervical region so that I would have to stop, address that and then return to the cranium. At times, starting in the cranium without first addressing some cervical vectors between C2 and C7 would result in an autonomic event where she would become flushed, begin gagging and eventually vomit, then break out in a sweat. It would take at least 10 minutes to calm her system down before we could work again. I believe this has something to do with the buccopharyngeal relationship to the pre-vertebral fascia and perhaps the impact her cervical dysfunction had on the vagus nerve. The cervical spine seemed to be pulled by both the cranium and the thorax, but it seemed like I had to “unstick” the fascia there in order to address the other regions. However, this could be because I am a novice that is learning about these vectors and perhaps this is truly a cranial driver and I just wasn’t quite correct in my treatment interventions.

- Diane’s comment:

This is exactly my experience with the pretracheal/buccopharyngeal/pericardial fascia vector – it is a complex one that often requires local release (as you note above) before the full line (sphenoid to diaphragm) can be addressed.

Unwinding the shoulder girdle by posteriorly rotating and slightly distracting the left clavicle fully corrected the position of the shoulder girdle but quickly brought on a strong gagging sensation and so correction was immediately released to avoid a full autonomic episode. The only other observation noted was that this correction did not impact C2 or C7.

Since TR 1&2 corrected in an auto-elongated position, they are unlikely the drivers and it could be clinically reasoned that manual corrections to this region are not necessary. However, due to the complexity of this case, I felt the need to be thorough. Manual correction of either TR 1 or TR 2 worsened the shoulder girdle, worsened the gag sensation, brought on a pull sensation to the crown of the head and created no observable change in the rotation of the cranium or sphenoid. Manual correction of TR 1 worsened TR2 and did not impact C2 or C7. Manual correction of TR 2 fully corrects TR1 and partially corrected C7 with no impact on C2.

- Diane’s question:

There is another visceral connection, other than the pretracheal/buccopharyngeal/pericardium we have been discussing that can explain why trying to manually correct TR1worsened the gag sensation. What structure attaches to the lung and the first rib and is in continuity fascially with the mediastinal structures?

- Stefanie’s response:

The continuation of the buccopharyngeal fascia that enters the thorax is the parietal pleura. This is also considered a layer of the endothoracic fascia which distally blends with the fascial of the diaphragm and forms the phrenico-oesophageal ligament. This ligament is thought to have an influence on the lower esophageal sphincter. I should note that, subjectively, this patient very often would report feeling like food would get “stuck” right above her stomach. More proximally, this fascia attaches to both the first rib and to C7’s transverse process. It also blends with the pre-vertebral fascia and the phrenopericardial membrane. This is all becoming so clear now!

- Diane’s comment:

And the parietal pleura attaches to the first rib and C7 via the suprapleural membrane.

FU#2 Driver Summary: The cervical region was considered the primary driver of FU# 2 with C2 & C7 noted to be priority segments. The cranial region was considered the secondary driver with the cranium (ICT and sphenoid) being the priority part of this region.

The reasoning for this decision was that a co-correction of C2 & C7 corrected all FU2 regions except for cranial region. Correcting the cranium (ICT and sphenoid) likely partially corrects C2 and C7 because those two segments correct all regions of FU #2 and the cranium improved neck position and provided relief from the gagging sensation.

- Diane’s comment:

I would switch this up! My feeling is that treating the vector that is sidebending the sphenoid (it likely goes to the diaphragm) first would allow her to elongate so much easier. I’d do this before the cervical spine. Thoughts?

- Stefanie’s response:

I’m inclined to agree based on the findings, but in practice I found that if I addressed the cranium 1st without addressing the cervical spine, her system would not respond as well. I believe her buccopharyngeal fascial restrictions, maybe even cervical instability may have led to a sensitized vagus nerve which required me to first work in her cervical spine, specifically addressing the pre-vertebral fascia. Considering the retropharyngeal space has the buccopharyngeal fascia anteriorly, the carotid sheath with the vagus nerve running laterally, and the pre-vertebral fascial posteriorly I think there was this lack of fascial gliding this cervical area exacerbating dysfunctions in the thorax and cranium. It was interesting because I would treat her cervical spine until a vector or her subjective reports would then lead me to the cranium. Then I could fully clear the vectors in the cranium and then would need to return to the cervical spine where I could then completely clear those vectors.

- Diane’s comment:

I don’t think we can identify a MSK driver in this case. Every correction made something else worse, and yes her best experience was with the cervical correction (her gag response was least); however, her head sidebending worsened. As mentioned above, I think this visceral system vector is compressing the entire MSK system from the cranium to the diaphragm, and maybe even lower, and needs to be treated exactly as you have described above before any MSK driver can be found – very similar to a dural system impairment. The pharyngeal plexus (CN IX and X) supply the upper and lower part of the buccopharygeal fascia so your hypothesis of the vagus nerve being involved is supported by the anatomy.

- Stefanie’s comment:

This is all so fascinating – I didn’t think to look into the neural innervation of the buccopharyngeal fascia.

A cranial region correction then resulted in full correction of the left clavicle, TR1 & 2 in their starting position, full correction of C7 and resulted in the best experience of the task. A correction at C2 fully corrected the clavicle, TR1 & 2 in their starting position and C7 in the starting position, but did not impact the OA joint or ICT and did not generate the same change in experience.

Functional Unit #3 (FU#3) Findings

This unit was not evaluated as the task did not involve use of the lower extremities.

Prioritizing functional unit 1 and 2 drivers

Manual co-correction of C2 & C7 partially corrected TR4, 5 & 6 as noted by the patient palpating and feeling a worsening in these rings on release of C2 & 7. TR4, 5, 6 could only be partially corrected manually, so it was not possible at this time to know if C2 & C7 would fully correct if these rings were free to move. Unwinding and centering of the cranium and sphenoid did not impact TR4,5,6 as noted by the patient palpating those rings. Manual co-correction of TR4,5,6 had no visually observable impact on cranium/sphenoid rotation but did worsen C2 and C7.

- Diane’s comment:

All of this is further evidence that the musculoskeletal system cannot ‘stack’ and align in the presence of this vector.

Final driver summary

Ms. L presented with a cervical (C2 & C7) primary driver and a cranial secondary driver (cranium (ICT/sphenoid priority). Since TR4, 5, 6 can only be partially corrected manually they have to be investigated further; therefore, in the context of this patient, they are considered a region of interest and not a driver.

- Diane’s comment:

In ISM the purpose of finding a driver is to determine the underlying system impairment requiring treatment. There are some system impairments that reveal themselves by not permitting correction of anything without significantly worsening another body region. I think this is the case you have here. It is very clear to me that the first impairment to treat is the visceral vector from the sphenoid to the diaphragm and that it will require local releases (cervical before cranial) before tackling the entire vector.

Further Analysis of the Drivers

Primary Driver: Cervical

Active mobility

Patient was unable to actively move her head to either side without co-contraction spasm of cervical rotators and a worsening of the position of C2 and C7

- Diane’s question:

C2 was left rotated, therefore active mobility testing would tell us how much right rotation she had at this segment with the goal being to get to neutral for unsupported sitting. Sounds like she had no active mobility of C2. Similarly C7 was right rotated, therefore active mobility testing would tell us how much left rotation she had with the goal being to get to neutral. Again, sounds like she had no active mobility of C7.

- Stefanie’s response:

Correct, she did not have active mobility at either C2 or C7

Passive mobility

Patient’s head and neck could not passively be moved more than a few degrees in any direction without spasms. Passive listening on release of cervical manual corrections used for further analysis. On release, C2 and C7 pulled inward and anteriorly toward each other.

- Diane’s question:

I’m confused. When finding drivers for FU#2 you said you could manually correct both of these segments and that when they were co-corrected, the shoulder girdle TR1 & 2 fully corrected. This is passive mobility. So could you, or could you not passively move C2 and C7 to neutral?

- Stefanie’s response:

My apologies, I don’t know what made me forget that passive listening #1 is the correction itself and instead I looked at passive mobility as only related to passive global motion of cervical rotation/flexion/etc. I could passively move C2 and C7 to neutral, I could not passively move her head and neck into rotation without global spasms. So C2 and C7 had passive mobility to neutral.

- Diane’s further question:

On release of the correction, the direction of the listening (anterior and inward towards each other) is highly suggestive of the vector I am thinking is causing a lot of this. Any idea what I’m thinking yet?

- Stefanie’s response:

That suggests the pre-vertebral fascia as a vector which has a link to the buccopharyngeal fascia

- Diane’s comment:

I’m not sure I can differentiate the pretracheal from the buccopharyngeal fascia from passive listening after releasing a correcting of C2 or C7 but for sure the listening took you into the visceral space where both of these are located! All of this story is pointing to this impairment so far.

Secondary Driver: Cranial Region – Cranium

Active mobility

Patient was unable to actively rotate or sidebend her HN to either direction. She could perform slight upper cervical flexion where posterior glide of the occipitals was noted equally bilaterally.

- Diane’s question/comment:

If you are considering the cranium in the cranial region as a secondary driver, we need to consider the intra-cranial mobility and not the upper cervical segments in the cranial region. Her start position was a left ICT, right rotated/left sideflexed sphenoid so your active mobility tests should have determined if she could come out of the LICT, if she could left rotated/right sideflex her sphenoid. Comment?

- Stefanie’s response:

I understand now, I was still thinking about global motions. My objective was to monitor her ICT with head and neck rotation, but she wasn’t able to do rotate so I looked at OA flexion to see if I noticed any unequal movement of her occipital condyles. Based on your explanation and my observations of this patient, she could not come out of the LICT or derotate her sphenoid actively.

- Diane’s comment:

Therefore, she had zero degrees of active mobility of either the posterior neurocranium (temporal bones and occiput) and sphenoid.

Passive mobility

- Diane’s comment/question:

Passive mobility testing comes first, then the listening information. Please tell us if you could neutralize the ICT and sphenoid positions. When determining drivers, you said you could and that the gagging reduced and her neck elongated. Therefore, I assume she has passive mobility of her ICT and sphenoid. Comments?

- Stefanie’s response:

Yes correct, with a better understanding of passive mobility for the cranium, I can confirm she has passive mobility of her ICT and sphenoid as I was able to get a complete manual correction of both.

On release of the cranial correction (distraction of the R greater wing of the sphenoid from the sphenosquamous suture to unwind the right rotation, lifting the L greater wing of the sphenoid to unwind the left sidebend and then derotating the temporal bones), the right greater wing moved first into right rotation with a short, strong vector toward the temporal bone that felt outside the cranium. Secondly, the left greater wing moved into L sidebending with a longer strong vector that felt like it was inside the cervical spine toward the throat; it did not feel long enough to reach the thorax. The R mastoid process of the temporal bone moved after the sphenoid in a posterior and medial direction (anterior rotation right temporal bone) with a short vector that pulled into the cranium. With further assessment of mastoid distraction, less movement of the mastoid on the occiput at the occipito-mastoid (OM) suture was noted on the L side because I believe it was already in a more lateral position due to its anterior rotation).

- Diane’s question:

In ISM, in intra-cranial biomechanics, the words “anterior rotation” are reserved to describe what the entire temporal bone is doing. When you say ‘anterior rotation’ in the last sentence of the prior paragraph, I think you mean that the left mastoid has moved anterior and lateral and not anterior rotation? Can you see the confusion??

- Stefanie’s response:

Yes, correct – I should have written it as “its anterior and lateral position”.

- Diane’s question:

What is your hypothesis as to the structure that caused the right rotation of the sphenoid into the squamous portion of the temporal bone? Was this a suture or something inside the cranium? If you think it was something inside the cranium, then you have missed a second part of this vector

- Stefanie’s response:

The vector pulling the sphenoid into RR felt very short to me and so I treated it as if it was the suture – when I released that vector the right rotation decreased and allowed me to address the L sidebend vector that pulled into the cervical spine area toward the throat.

- Diane’s comment:

I also believe that you have missed the sideflexion vector of the sphenoid. What was causing it to sideflex left? Did you feel it sideflex left at all when you released this correction?

- Stefanie’s response:

Yes, I’m sorry I neglected to address this. I mentioned treating this vector in my treatment area but did not write it here. I expected the vector to pull inside the thorax, but it actually felt like it pulled more inside the cervical spine stopping around the throat. My theory was the resistance was a pull from the buccopharyngeal fasica that was, for lack of a better term, stuck at the level of the retropharyngeal space but likely continued into the thorax because when correcting the cervical spine, she felt discomfort in her thorax and upward into her face.

- Diane’s comment:

It is very common for the sphenoid to have a very short vector of pull into the sphenosquamous suture (SSS) when there is congestion in the anterior part of the cerebellar tentorium. Treatment of this would involve distraction of the (SSS). No way through this report to confirm if there was an intra-cranial component to the passive listening! Another reason I suspect there was congestion in the right side of the cerebellar tentorium was the 3rd listening from the right temporal bone “The R mastoid process of the temporal bone moved after the sphenoid in a posterior and medial direction (anterior rotation right temporal bone) with a short vector that pulled into the cranium.” This is a vector of pull from the transverse sinus.

Area of interest: Thorax (required further analysis because they could not be manually corrected) TR4, 5, & 6

- Diane’s question:

Given our conclusion above, that the pretracheal/buccopharyngeal/pericardial fascia is causing compression from the cranium to the diaphragm, do you think the best next step is further analysis of these rings of interest? You have already determined the first system impairment to treat. You state below that she has limited global active ROM of the thorax to either side. In clinical practice, would you really be going into further assessment of these rings at this point, or would you start treating that visceral vector?

- Stefanie’s response:

I would start treating the visceral vector. In this particular evaluation, I wasn’t fully seeing the picture and was fighting my “instincts” to make sure I covered everything. Everything I was finding was telling me there was a visceral component, but my newness to ISM and insecurities made me question myself and resort back to the “rule” of if you cannot correct a segment, you need to clear it first before continuing. As you note below, when I did further evaluate these rings, the vector analysis led me to the viscera anyway and help me confirm my original hypothesis. In sessions that followed, I addressed the thorax with the intent to work on the visceral fascia and not in regard to joints.

- Diane’s comment:

When learning and integrating a new/different model into practice, it is always good to ‘triangulate your findings’ – this way each model informs the other when there is ‘a truth’.

TR4 RR, translated L

Active mobility

(assessed via breathing as patient had limited global active ROM into rotation to either side)

TR4 – the right 4th rib was posteriorly rotated and the left 4th rib was anteriorly rotated: There was very little, if any motion felt at this thoracic ring. The asymmetry between the two sides did not significantly increase or decrease during breathing indicating dysfunction impacting both sides of the ring.

Passive mobility

Only able to partially correct each segment passively. With manual correction, I could achieve roughly a 50% correction of TR4

- Z joints: R T3-T4 more extended and L more flexed

- Restriction of inferior glide of L Z joint

- Restriction of superior glide of R Z joint

- CT joints:

- Restriction of inferior glide/posterior roll of 4th L CT

- Restriction of superior glide/anterior roll of 4th R CT

TR5&6 LR, translated R

Active mobility

(assessed via breathing as patient had limited global active ROM into rotation to either side)

TR5 – the right 5th rib was anteriorly rotated and the left 5th rib was posteriorly rotated

- Inhalation: Increased the asymmetry between the right and left rib

- Exhalation: Decreased the asymmetry between the right and left ribs but they did not become fully symmetrical

TR6 – as with TR5, the right 6th rib was anteriorly rotated and the left 6th rib was posteriorly rotated

- Inhalation: Increased the asymmetry between the right and left rib

- Exhalation: Decreased the asymmetry between the right and left ribs but they did not become fully symmetrical

Passive mobility

Only able to partially correct each segment passively. With manual correction, I could achieve roughly a 50% correction of TR5&6

- Reduced L translation (possibly due to compression of TR 4 & 7 on the left)

- Z joints: R T4 – T6 more flexed

- Restriction of inferior glide of R Z joints on T4-T5 and T5-T6

- CT joints:

- Restriction of inferior glide/posterior roll of 5th & 6 R CT

Patient subjectively reported feeling better after thoracic joint mobilizations, segments demonstrated slight increase in manual correction with ability to correct to about 75%, but segments were still not able to be fully corrected.

Passively listening: On release of TR 4,5,6 manual co-correction TR6 was noted to move first. When isolating TR6 correction, the R portion of the ring moved first and was pulled anteriorly, medially, and inferiorly with what feels like a strong, long vector indicating a myofascial system impairment toward the hiatal opening area of diaphragm.

- Diane’s comment:

Even this is taking you to the visceral impairment!

Case Summary

Ms. L is complex with a highly compressed system which at its core seems related to fascial restrictions. Specifically, there are restrictions in the pre-vertebral fascia and most notably the buccopharyngeal fascia that create compensatory rotations and compression through the cranial, cervical and thoracic regions. These findings may be related to her medical diagnoses. A recent study by Wang and Stecco (2021) noted individuals with EDS had thicker deep SCM fascia when compared to healthy controls. Although not specifically articulated in the article, it appears they are discussing the superficial laminae of the deep cervical fascia. It may be possible that all layers of the deep cervical fascia exhibit similar thickness which can begin to explain the findings within this patient case. There have been sessions where the cranial and cervical segments noted in this report are found rotated in opposite directions than what has been described here. There are also sessions where the patient presented with a full or partial infinity sign without any head trauma. Persons with hypermobile EDS are prone to intracranial hyper and hypotension (Severence et al 2024). Subjectively, Ms. L has noted vein distention in her face during onset of neurologic symptoms. Those symptoms resolved quickly and imaging has not provided any rationale. It was my theory that her seemingly spontaneous infinity signs could be related to an imbalance in CSF drainage due to cranial torsion. These incidences, since treating the aforementioned drivers, have resolved.

- Diane’s comment:

All of this makes so much sense to me Stefanie. Drainage will be significantly impacted in all fluid systems for this client.

Treatment

Release/Align

- Cervical: pretracheal & buccopharyngeal fascia release performed starting with C2 – pulling the trachea & esophagus together with the anterior (pretracheal) and posterior (buccopharyngeal) fascia toward C2 until a release was felt (the release was a softening both in C2 and in the trachea/esophagus & fascia) then pulling them away from each other. Technique repeated for C7

- Cranial:

- Sphenoid

-

-

- R SS suture released for sphenoid

- L sphenoid greater wing released from the greater wing to the hyoid and then to the trachea around the level of the larynx.

- All areas were released by shortening the vector and then lengthening with breathing

- R posterior cerebellar tentorium release

-

- Thorax: Mobilizations performed until joint motions were found to be optimal but long vectors remained. Patient placed in L sidelying as TR 6 (translated R) was found to move first. L anterior diaphragm was pulled toward TR6 then the segment was stacked and the diaphragm was pulled away until a release was felt. However, a long internal vector remained. Barral technique of anterior to posterior compression was applied to the rib cage around TR 6 and then, as a thoracic unit, assessed for greatest tension as it was pulled away from the viscera. A strong vector was noted when the rib cage was moved in a superolateral direction. That position was held while patient took deep breaths until a release was felt. Procedure was repeated for TR 4 with patient in right sidelying. TR4&7 along with TR5&6 were not fully corrected but demonstrated more optimal ABC when patient was reassessed.

- Diane’s comment:

One day when you attend an ISM update course, I’ll show you how I address this vector by releasing any restrictions in the retropharyngeal space first, then sphenoid to TR2 (which often has an incongruent rotation between the manubrium and the ribs of the 2nd ring and on the inhale breath the manubrium cannot nutate relative to the left and right clavicles, rather it gets ‘sucked into’ the thorax and the ribs follow the inward motion), then sphenoid to TR6, then sphenoid to diaphragm. I stack correct the hard frame incrementally between the two points I’m working on and us the held (3-5 seconds) inhale breath until I feel an auto-elongation between my hands. Goal is the same – get this vector to lengthen and allow auto-elongation from cranium to TR6 with no worsening elsewhere! This technique isn’t in the ISM Flow course yet.

- Stefanie’s Comment:

That would be amazing!

Connect/move

Patient donned compression garments and an external cuing device called a body braid which helps individuals with EDS enhance their proprioceptive input. This was used prophylactically as the above release techniques fully restored her motor control, allowing her to easily sit unsupported with near optimal ABC and without any sensations of gagging, or air hunger. In addition, she was able to actively turn her head and neck with optimal ABC through 75% of her range. Passively she had full ROM with optimal ABCs of head and neck rotation. Patient was able to maintain optimal ABCs and experience little to no gagging sensation with arm and leg movement while sitting unsupported.

Home exercise practice plan

Patient was provided with instructions on how to maintain the release of the pre-tracheal/buccopharyngeal fascial as well as her R SS suture. To self-mobilize TR4, the patient would have to lie on her right side and rotate left while using the compression from the ball to help move TR4 into left rotation. To self-mobilize TR6, the patient would lie on her left side, compress using the ball and rotate to the right pulling TR6 with her. Unfortunately, patient compliance is not 100% because she at times cannot move her hands to her face without compromising her cervical position.

Follow-up treatment sessions

Ms. L continued to be a complex case and her drivers did change, but the clinical picture did not.

She remained with a primary driver of the cervical spine and a secondary driver of the cranium. However, the priority segments of the cervical spine changed and she did at times present with a partial infinity sign and once with a full infinity sign. Since treating the full infinity sign her atlas was found translated left and right rotated with C7 translated right and left rotated. Her thoracic findings remained the same and her cranium was most typically in a L ICT with an incongruent right rotated and left side bent sphenoid but at times demonstrated a L ICT with a congruent sphenoid.

She remained with buccopharyngeal fascia involvement that continues to impact her down to her hiatal hernia and up to the crown of her head. In addition, new influences of cranial nerve tension in CN5 and CN 9-12 were discovered that, when released, restored full cervical rotation ROM and control in either direction with new found ability to move her tongue and jaw in full cervical rotation. The release also alleviated any lingering gagging sensations with head movement while sitting unsupported. The thoracic rings continued to require release from visceral vectors likely related to the buccopharyngeal fascia.

Patient made significant progress despite the remaining lack of optimal ABCs. She can tolerate car rides for up to 20 minutes where previously she could only tolerate 5 minutes at most. She has had incidences where her wheelchair hit a large bump and she did not experience any autonomic distress such as grey outs, pain, or restricted breathing. She was able to recover from incidences that bring on autonomic distress within 1 PT session where in the past it took 2-3 sessions.

The most recent treatment session included

- Release and alignment of the cranium, cervical and thoracic regions via release of all fascial, suture and cerebellar tentorium vectors.

- Connect: sitting posture with auto-elongation while wearing compression garments

- Move: seated unsupported with auto-elongation, cervical rotation, and tongue movement

Ms. L has now graduated with a degree from Columbia University and moved to Hawaii with her partner who is pursuing a PhD and a career with NASA. Ms. L reports that prior to starting PT with an ISM focus, she was so disabled that she considered abandoning her studies and returning home to California to receive cervical spine stabilization surgery. She credits the physical therapy received in New York as the key to her success and improved functionality. It is unknown at this time if the effects are long-lasting or if she will experience greater disability without continued PT focusing on these drivers.

- Diane’s comment:

Such an amazing case which illustrates the integration of ISM, EDS, POTS, MCAS brilliantly. I hope she can find such great care in Hawaii. Well done Stefanie.

- Stefanie’s Comment:

Thank you, Diane, this has been an incredible learning experience and without ISM I don’t know if I could have worked all this out.

References

Wang, T.J; Stecco, A. (2021). Fascial thickness and stiffness in hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 187(C). 446-452.

Severance, S., Daylor, V., Petrucci, T., Gensemer, C., Patel, S., & Norris, R. A. (2024). Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and spontaneous CSF leaks: The connective tissue conundrum. Frontiers in Neurology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1452409

Mnatsakanian A, Minutello K, Black AC, et al. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Retropharyngeal Space. [Updated 2023 Jul 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537044/

Sutcliffe P, Lasrado S. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Deep Cervical Neck Fascia. [Updated 2023 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541091/

Skills Demonstration

Case Study Author

Clinical Mentorship in the Integrated Systems Model

Join Diane, and her team of highly skilled assistants, on this mentorship journey and immerse yourself in a series of education opportunities that will improve your clinical efficacy for treating the whole person using the updated Integrated Systems Model.

We will come together for 3 sessions of 4 (4.5) days over a period of 6-8 months with lots of practical/clinical time to focus on acquiring the skills and clinical reasoning to put the ISM model into practice. Hours of online lecture and reading material and 12 hours of in-person lecture are...

More Info

This was something that really fascinated me as well – we have the spasm, pain, an increase in pulse, and vision loss. My first thought was something triggered the autonomic nervous system via irritation/facilitation/slight compression of the vagus nerve. This could be due to the spasm itself or to the cause of the spasm which is likely her cervical instability. The muscle that is rotating her trachea is tricky. She is subjectively reporting that her trachea feels like it is rotating in these moments, but she often places her hand on her cricoid cartilage. The few times I was able to witness this happening, it appeared to shift to the left more so than rotate. With passive correction and vector analysis of the cricoid cartilage/trachea, I felt a resistance pulling to the left and very slightly upward. Based on that, the main muscle I suspected was the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle since there are insertions into the cricoid cartilage and has an orientation that would pull up and back. Interestingly enough, this muscle is innervated by branches from the both the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves. However, this pull may also be related to buccopharyngeal fascia (BP) restrictions as both the trachea and esophagus are enveloped by a continuation of this fascia.

This was something that really fascinated me as well – we have the spasm, pain, an increase in pulse, and vision loss. My first thought was something triggered the autonomic nervous system via irritation/facilitation/slight compression of the vagus nerve. This could be due to the spasm itself or to the cause of the spasm which is likely her cervical instability. The muscle that is rotating her trachea is tricky. She is subjectively reporting that her trachea feels like it is rotating in these moments, but she often places her hand on her cricoid cartilage. The few times I was able to witness this happening, it appeared to shift to the left more so than rotate. With passive correction and vector analysis of the cricoid cartilage/trachea, I felt a resistance pulling to the left and very slightly upward. Based on that, the main muscle I suspected was the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle since there are insertions into the cricoid cartilage and has an orientation that would pull up and back. Interestingly enough, this muscle is innervated by branches from the both the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves. However, this pull may also be related to buccopharyngeal fascia (BP) restrictions as both the trachea and esophagus are enveloped by a continuation of this fascia.