Patients Story

Mr B. is a 52-year-old and has been a whole-time Firefighter and a part-time Personal Trainer for the Fire Service since 2005. Previously a self-employed full-time Personal Trainer, Mr B. considers himself to be in reasonably good health. In 2015, Mr B. first reported left shoulder and left-sided low back pain when wearing Breathing Apparatus (BA) Kit. During the initial assessment in 2015, Mr B. demonstrated limited range of motion (ROM) of the left shoulder joint, the left innominate was locked in a neutral position (no passive anterior and posterior motion), coccyx pain left-side during palpation, and a positive test during the Active Straight Leg Raise on the left. With the skills, available to me at the time, Mr B. was treated for over-active left iliocostalis using dry needling and given some motor control exercises for the left-side lumbopelvic hip complex. Re-test demonstrated improved passive movement of the left innominate and improved ROM of the left shoulder joint.

Diane’s question:

- For clarification, and given the known anatomy of the SIJ in a 52 year old male, can you describe the mechanism that is occurring at his SIJ that led you to use the term ‘locked’? What has locked the joint in neutral?

- A positive ASLR test usually means that the effort to lift the leg improves when compression is applied to the pelvis (Mens et al 1999). This often means that the force closure mechanism across the SIJ are insufficient and the compression controls shear of the joint during loading, and thus facilitates the ease of performing the task. Yet, this doesn’t fit with the use of the term ‘locked’ whereby regardless of the mechanism, it appears that there is too much compression across the left SIJ. Yet, findings are findings! How do you explain the conflict here?

Jo’s response:

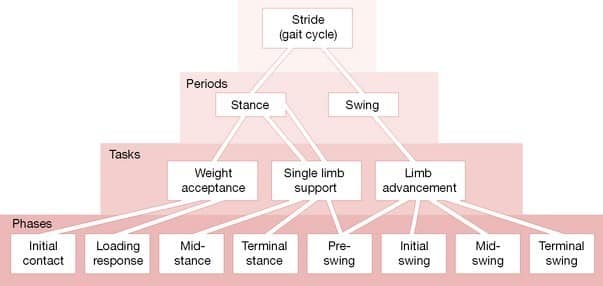

My mistake, it should have read ‘the gait biomechanics are locked in heel-strike position of gait, commonly termed ‘Weight acceptance’, (see Figure 1) therefore contributing to a functionally shorter leg on the left, estimated 14mm discrepancy. When discussing gait biomechanics I shall be referring to all mechanisms from the lumbar spine to the foot.

Although the Content Validity of these tests are still being studied, currently, the evidence suggests high specificity and sensitivity. Therefore, if Mr. B. is locked in heel-strike position within the gait cycle, this may suggest that he has lost capacity for the other two specific tasks of functional gait:

- mid-stance/foot flat (Single Limb Support) and

- heel off (Limb Advancement).

Here on in I shall refer to the Tasks of gait as shown in Figure 1.

Perry (1992) suggests ‘Single Limb Support’ task (48% Gait Cycle) mechanisms are to dynamically support body weight (limb and trunk) in both sagittal and coronal planes, whilst ‘Limb Advancement’ task (40% of Gait Cycle) demands preparatory posturing through swing phase (x4 postures identified in Phases – Figure 1) both these tasks require the capacity for dynamical systems (I think in Manual Therapy it is termed ‘tensegrity’?). During ‘Weight Acceptance’ task (0-12% of Gait Cycle) which is the most demanding albeit shortest task during the gait cycle, this task is essential for; shock absorption, initial limb stability and the preservation of progression. Three forces act on the joints; falling body weight, ligamentous tension and muscular activity. At Weight acceptance body vectors are anterior to hip and posterior to knee, flexion torque is created in both joints to necessitate active extensor muscle response to restrain the fall of body weight. Continued advancement of gait (Single limb support and Limb advancement) should have specific biomechanical attributes which would be lost if locked in Weight acceptance;

- reduction of flexion torques at the hip and knee

- passive extension of the hip

- postural instability through stance where muscle action is directed towards decelerating the influences of gravity and momentum that create flexion torques at the hip and knee and dorsiflexion torques at the ankle all of which threaten standing stability.

If these tests are valid and reliable, they are suggesting Mr B. does not have the capacity to perform optimal gait, which may suggest increased non-optimal forces are applied to his body. Where? When? How? Why? Drivers? Remain under question. Currently, I have a retrospective and prospective study (18 months of data collection, 800 people so far) exploring what, if anything, does this all mean i.e. what site on the body is most at risk, what is/are the driver(s), and relative dose exposure (how long do they continue to move with these dysfunctions before they get an injury).

My hypothetical deductive reasoning leads me to believe he has lost dynamical capacity for optimal gait on his left. This locked ‘system’ lacks the fundamental motor control and muscle physiology to create dynamic stability through gait.

Whilst I appreciate the Content Validity of the ASLR test, I use it to explore relationships of a person’s capacity to complete functional tasks of gait.

My theory with Mr. B. is whilst he is ‘locked’ in weight acceptance his muscle physiology is held short and rigid with no ability to extend the hip without it being visually apparent to the tester i.e. torso rotations and ‘gripping’ and when compressing the ASIS’s Mr. B. was able to complete the ASLR test with ease. Why? Does this compression create changes in mechanical levers of specific muscles? Does it facilitate some neural input? No idea – but compression of the ASIS’s has high correlation with subjects locked in Weight acceptance task of gait and changes their ASLR perceived effort from positive to negative.

Diane’s response:

Whoa!! Great info here Jo. Is it fair to say in simple physiotherapy biomechanical terms that his left innominate was then held in posterior rotation relative to the left side of the sacrum; however, it was not an articular fixation since compressing the ASIS’s together (as in the ASLR test) changed his motor control strategy around the SIJ and enabled him to use less effort to left a straight leg?

Jo’s response:

Yes, I believe somehow the compression is allowing the subject the capacity to then raise the leg with less effort.

Diane’s note to reader:

When Jo uses the term ‘locked’ in this report, she is not referring to a joint fixation but rather to a motor control strategy that does not allow the joint to move optimally as it should.

Currently he reports to have left-sided low back pain which was triggered by a left ankle inversion incident whilst carrying a TV from a building 1st May 2016 (wearing Fire Boots and Breathing Apparatus). At the time of the incident he felt a ‘clunk’ around the left sacroiliac joint (SIJ), and as soon as the TV was put down he felt an immediate gripping sensation down the lateral left-side of his body (buttocks to foot).

Most daily activities e.g. sitting down, walking and standing cause left buttock pain.

Mr B. sought out the support of a Chiropractor, Consultants, Pilates, various strength, conditioning, and stretching programmes all with varied outcomes;

- May 2016: deep buttock pain and sciatica left leg.

- June 2016: during light deadlifts, Mr B. reported feeling a ‘popping’ sensation in his low back, then he felt a ‘different’ back pain (points to T11/T12 area on the left) with the left-sided back muscles going in to spasm and intense lateral left leg pain (buttocks to foot) and sciatica whole way down the back of the left leg.

- July 2016: Mr B. saw a Chiropractor privately who diagnosed a locked left SIJ which was irritating the facet joints in the lumbar spine. Post manipulative treatment of the pelvis, Mr B. started to feel much better and therefore he progressed with strength training and rowing (Concept II).

Diane’s comment:

who knows what the chiropractor thought a ‘locked’ SIJ joint was!

- August 2016: Mr B. noticed a lump above his left SIJ when lying on his back which he believes is blocking his ROM in spinal extension and spinal lateral flexion to the left.

- November 2016: Mr B. admitted himself into Accident and Emergency at the local Hospital with pain in his stomach referring through to his low back on the left. Doctor diagnosed the pain was due to taking too many pain killers and anti-inflammatories for an extended period of time (these were the medication that was prescribed by the Doctor).

- December 2016: walking became difficult and was unable to stand upright for more than 2 minutes due to the lump in his low back left-side. Numbness and cramping in toes, inability to stand whilst urinating and control the flow of urination, pain in the left gluteal area migrating to anus, whilst lying supine triggers searing pain around the anus – All Manual Therapists suggested Mr B. immediately admit himself in to Accident and Emergency for further investigations, of which he did and was dismissed from Hospital with pain medication.

- February 2017: Sleeping on bed fully clothed on tummy as couldn’t physically get in to bed. Appointment with Consultant Specialist, MRI diagnosed three bulging discs; L5/S1 (mild central protrusion), L5/L4 (significant protrusion left), and L4/L3 (mild protrusion right).

- February 2017: Mr B. explored the internet for answers and came across the ‘Posture Doctor’ who spoke about similar symptoms Mr B. was experiencing and the answer would be in completing strength and conditioning on the gemellus inferior and superior. Post-exercise Mr B. could stand tall with lots of pressure relief in the spine.

- March 2017: Mr B. had an appointment with a Consultant Specialist regarding the MRI results. He was advised to continue with the rehabilitation programme and was put on the emergency list for epidural and/or discectomy.

Currently, Mr B. reports the lump left-side of the spine is no longer present, sciatica has been absent for 1 month, allowing him to eliminate all pain killers and anti-inflammatories. He currently struggles with a weak low back during spinal flexion and for one month a new symptom of a ‘tight tearing’ feeling down the anterior aspect of the right thigh. Mr B. continues to complete the exercises from the Posture Doctor and is not receiving any treatment from any Manual Therapists.

Mr B. reports two incidents of tearing the right hamstrings during rugby in 1980 and 2005. During this time (1995) he was involved in a Quad bike incident and fell 50-60ft downhill and was knocked unconscious. He also reports tearing the right biceps brachii at two separate occasions between 2000 and 2005 during rugby tackles.

Narrative Clinical Reasoning from the Story

Listening to Mr. B’s. experiences since his first visit in 2015, suggests the ‘drivers’ of his symptoms may not have been fully identified – almost as if the body is trying to self-correct, poorly – and therefore causing Mr. B. more issues.

Diane’s question:

Given your knowledge on contemporary theories on motor control adaptation and pain, what other explanation could there be for the recurrent episodes of acute lumbosacral pain?

Jo’s response:

Central sensitisation? The nervous system goes through a process called wind-up and gets regulated in a persistent state of high reactivity. This persistent, or regulated, state of reactivity lowers the threshold for what causes pain and subsequently comes to maintain pain even after the initial injury might have healed (https://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/understanding-chronic-pain/what-is-chronic-pain/central-sensitization).

Diane’s response:

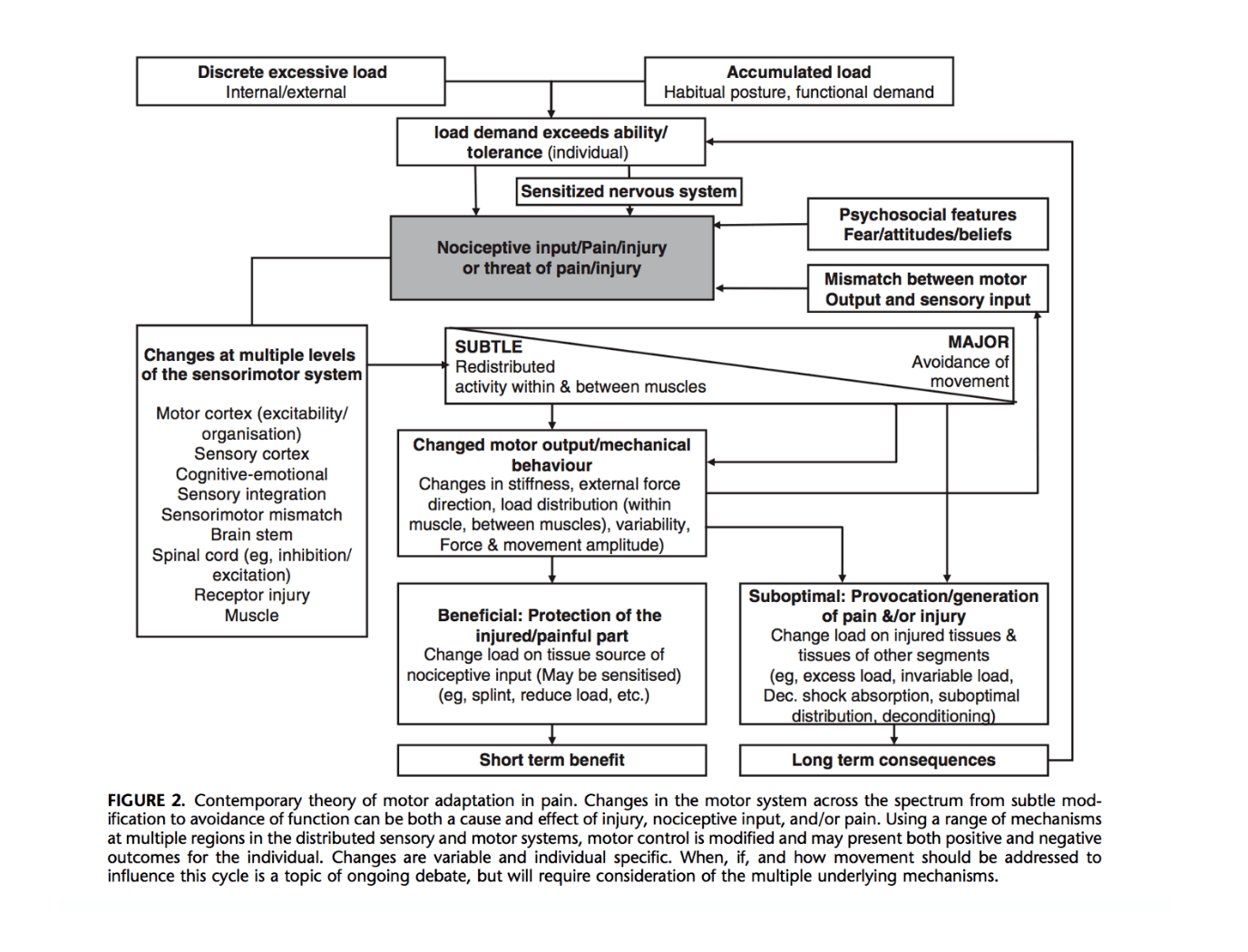

Hodges & Smeets (2015) summarized all that is known to happen in the CNS and PNS in this great figure from their article. In addition to sensitization at a central level, there is often a redistribution of muscle activity with under-activity of the deep segmental muscles and over-activity of the superficial muscles. This pattern results in poor segmental lumbar control – a biologically plausible mechanism to explain Mr. B’s recurrent back pain.

Jo:

Thank you Diane. I have downloaded and will read the paper.

Meaningful Complaint

At the initial assessment, Mr B. complained of three areas of concern for him:

- A feeling of central weakness in the low back during standing and walking.

- A constant ‘tight tearing’ sensation anterior right thigh: proximal to distal when squatting.

- A constant tightness in the posterior ribs and low back area on the left during squatting.

Meaningful Tasks

- To be able to put on and wear full fire kit (includes breathing apparatus). From stepping in to his fire trousers (boots already in fire trousers) pushing his feet in to the fire boots, pulling on his fire jacket and then lifting the Breathing Apparatus (BA) from the floor with his left-hand and swinging the BA kit on to his back. To complete all steps with no concerns.

Cognitive and Emotional Beliefs

Mr B. is very keen to return to full operational duties (currently on limited duties) as he is concerned about the amount of time he has been off work (a total of 72 days) due to the start of these symptoms May 2016. He also believes there is something ‘wrong’ with the left SIJ, and that this is the cause of all his symptoms since initial onset in 2015. Mr B. believes he is ready to return to full operational duties due to his symptoms being less significant and being more able bodied. Mr B believes that he is ‘in this state’ due to having ‘pushed’ himself too hard when he returned to physical training post previous appointments with myself (October 2015).

He has trialled wearing the breathing apparatus to test his body and finds after a minute of wearing the full fire kit that he starts to get pain in both SIJ’s, right anterior hip area and left low back/ribs. Mr B. believes that a couple sets of deadlifts every day has kept him in ‘good-shape’ prior to 2015 and has completed this routine for the last 23 years and wants to continue. Mr B.’s ultimate goal is to be able to move freely without needing to think about gripping through the spine before he moves.

Further Narrative Clinical Reasoning

Having worked for the Fire Brigade for 4 years, this is a common Firefighter’s belief. Taking time off-work is discouraged and the Firefighters receive pressure from the occupational health department to get back to work quickly due to cost implications. Although Mr. B. feels much better my question remains: “Does he have the capacity to complete firefighter specific tasks with minimal risk to himself and his crew”? Ensuring my language is clear and concise to avoid any misconceptions on his abilities is primary in these appointments.

Diane’s question:

Did you ask him what he meant by something being ‘wrong’ with his SIJ? What does he understand can go wrong with the joint?

Jo’s response:

This was a strange one. When I asked him what he meant by this he said he just feels like its weak and it’ll give way on him at any time, without warning. When I explained the biomechanics of the joint to him he seemed to need time to let the new information settle. He has a very strong Personal Trainers Education and sometimes struggles with challenges to his existing belief systems – which is that the SIJ does not move. I referred him to your book and some tutorials on YouTube with some papers on PubMed all explaining the anatomy of the SIJ and its biomechanics.

Diane’s response:

Strange indeed, that someone would consider the SIJ not able to move and yet feels it is ‘weak and will give way on him at any time’. A conundrum; however, I think you managed it well.

Screening Tasks

2023 Diane’s comment:

A reminder that this report was written in 2017. 6 years later and ISM has evolved! We now find drivers in functional units and then do quick screening tests to determine if evaluation of another unit is required. If it is, we then find that unit driver and the prioritize the two unit drivers. This avoids the long list of findings so common when we didn’t use to do this! Also, we don’t find drivers in the start screen position which here is Quiet standing for Mr. B. It’s been interesting to go back to 2017 when Jo wrote this to see how fine-tuned ISM has become!

- Quiet standing (where is Mr. B. in standing to know where he goes when moving)

- Weight transfer (balance from one leg to other – simulating stepping in to trousers)

- Squat Task (initiating squat to put trousers and boots on)

- Deadlifts!

Jo’s comment:

At this point Mr B. and myself needed to understand if this exercise is conducive for him during his rehabilitation therefore we completed a task specific screening – he was adamant that this exercise ‘saved’ him from further complications – it’s like his heroine! We needed to explore.

- Cranium & Cervical spine (Csp): Intracranial torsion left, cervical spine side-bent to the left, 2nd and 3rd cervical vertebrae translated right/rotated to the left. The position of the cranium, C2 and C3 are congruent.

- Thorax: upper and lower thorax rotated to the right in the transverse plane and associated with the 2nd, 5th, 7th and 9th thoracic rings translated to the left/rotated to the right which are incongruent with the cranium/upper neck.

- Shoulder girdle: left humeral head anteverted (forward) with the left scapula medial border winging. The right shoulder complex FLT’s are incongruent. Collectively the shoulder girdle torsion is to the right, which is congruent with the transverse plane rotation of the upper thorax. However, there is an incongruency within the right shoulder girdle in that the scapula is downwardly rotated while the right clavicle is anteriorly rotated.

Jo’s question:

If the medial border is winging, does this not add torsion to the left? So collectively the shoulder would not be in torsion to the right?

Diane’s answer:

If the left clavicle is anteriorly rotated relative to the right, this pattern is associated with a right shoulder girdle torsion. Medial border winging of the left scapula (internal rotation) would also be congrugent with right torsion

- LumboPelvicHip Complex (LPHC): The pelvis is rotated to the left in the transverse plane with a congruent IPT

Diane’ comment:

After further discussion below, the right SIJ may in fact have been unlocked in standing and therefore, there would not be an IPT. Although the findings with respect to SIJ control on the right were noted to change with varying tasks, so perhaps sometimes it was an IPT and other times an unlocked SIJ. That is the consistent feature of a motor control deficit – inconsistency.

The transverse plane rotation of the pelvis is incongruent with both the lower and upper thorax but congruent with the cranium and upper cervical segments. Left femoral head anteverted (forward). Lumbar spine side-flexion to the left with a notable hinge at L4/L5.

Diane’s question:

Can you comment on the difference between an intrapelvic torsion (IPT) and an unlocked SIJ?

Jo’s answer:

An unlocking SIJ is a sign of failed load transfer in the sacroiliac joint where increased load applied to the joint has caused the joints positional integrity to fail. An intrapelvic torsion (IPT) is where the joint does not fail but rather the osteokinematics of the sacrum relative to the left and right innominates are either congruent or incongruent with the transverse plane rotation of the pelvis.

Diane’s further question on this question:

When the pelvis is positioned in an IPT both sides of the sacrum are nutated relative to the innominate. When the pelvis has an unlocked SIJ the sacrum is counternutated relative to the innominate. Fill in the blank.

Diane’s question:

Is the left hip position congruent or incongruent to the TPR of the pelvis?

Jo’s answer:

Incongruent

Diane’s question:

Is there an associated IPT of the pelvis or does he stand with one SIJ in an unlocked position?

Jo’s response:

He stands in an unlocked position

Diane’s response:

Hm…. You said… “The pelvis is rotated to the left in the transverse plane with a congruent IPT”. The pelvis can’t be both in an IPT and at the same time have an unlocked SIJ. Which one?

Jo’s response:

Oh man! Sorry. Unlocked SIJ NOT congruent IPT.

Diane’s response:

Below Jo notes that the right SIJ unlocks early in a right weight shift task; however, later she notes that the right SIJ gives way during a squat task. It could be that he is not unlocked when weight is equally shared between his left and right legs and that as soon as load increases slightly (right weight shift and/or squat) the right SIJ gives way or unlocks.

- Knees: Unremarkable.

- Feet: Right calcaneus and forefoot inverted; mid foot optimal, poor windlass mechanism 1/5. Position of the foot is incongruent to that of the pelvis.

Diane’s comment:

You are correct that the foot is incongruent to the position of the pelvis because a left TPR of the pelvis should induce pronation of the right foot. Hindfoot inversion and forefoot inversion, or external rotation, are not part of a pronated foot pattern. A pronated right foot would see the hindfoot everted and the forefoot ‘fanned’ – if the foot was adaptable.

Diane’s comment:

Jo – I’m not sure that I understand the grading here of the windlass mechanism? Is this a strength measure or something else?

Jo’s answer:

It is a resistance test (subject in Quiet Standing): 1/5 no resistance at the hallux, 5/5 inability to dorsi flex the hallux, ideal 3/5

Diane’s comment:

So this is a different strength grading scale than what we use in physio (Kendall) correct?

Jo’s response:

I’m not sure, I haven’t learnt the test from Kendall so I am not familiar with this.

Diane’s question:

Can you provide us with the reference or information as to where this windlass grading test is from?

Jo’s response:

This test assesses the Windlass Mechanism (Hicks, 1954). Jacks test or the Hubscher’s maneuver. The test is performed with the patient weight bearing, with the foot flat on the ground, while the tester dorsiflexes the hallux and watches for an increasing concavity of the arches of the foot. A positive result (arch formation) results from the flatfoot being flexible. A negative result (lack of arch formation) results from the flatfoot being rigid. These tests are graded from 1 to 5 on tension in the mechanism of the test. Grade 1 = loose, no control. Grade 5 = inability to raise hallux. In a Jack’s test, the patient raises the rearfoot off the ground, thus passively dorsiflexing the hallux in Closed Kinetic Chain. This will result in an increase of the arch height in cases of Dynamic (Flexible) Flat Foot. If the deformity is a Static (rigid) Flat foot, the height of the arch will be unaffected by raising up the heel on the forefoot. It is also one method of diagnosing functional hallux limitus. recent investigations into its reliability have questioned its ability to predict range of motion at the 1st MTP during Gait.

Reference; Diagnosis and treatment of adult flatfoot. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery, Volume 44, Issue 2, Pages 78–11 M. Lee, J. Vanore, J. Thomas, A. Catanzariti, G. Kogler, S. Kravitz, S. Miller, S. Gassen

2023 Diane’s comment:

Today we would not find the driver for the start screen position of quiet standing, unless standing was also a meaningful task for this individual.

Finding Drivers in Quiet standing:

- Correcting the cranium made the alignment of the thorax (2nd, 5th, 7th, 9th thoracic rings) and the pelvis worse.

- Correcting the CSp made all sites of FLT worse

- Correcting the left hip improved the alignment of the upper thorax and pelvis but made the alignment of the low thorax and CSp worse.

- Correcting the 2nd thoracic ring made the alignment of the CSp and pelvis worse.

- I was unable to correct the 5th or 9th thoracic rings.

- Correction of the 7th thoracic ring improved the alignment of the CSp and 5th and 9th thoracic rings but made the pelvis and left humeral head worse.

- Correcting the right calcaneus made the thorax worse.

- Correcting the left hip and the 7th thoracic ring improved the alignment of the rest of the thorax, the pelvis, Csp, cranium and pelvis.

Outcome: Co-Driver thorax (7th thoracic ring) and left hip.

Squat task

- Cranium & CSp: No change from Quiet Standing.

- Thorax: 5th, 7th and 9th thoracic rings translated further to the left/rotated to the right no change in position of the 2nd thoracic ring.

- LPHC: During the squatting task bodyweight distributed evenly, the LTPR of the pelvis increased immediately and there was no loss of SIJ control nor IPT. The left femoral head centred during the squat and then anteriorly translated as he returned to standing. Lumbar spine mechanics unremarkable.

Diane’s comment:

Going down into the squat resulted in an increase of the left transverse plane rotation of the pelvis, yet this was not associated with either an intrapelvic torsion (usually occurs in conjunction with a TPR), nor any giving way of the SIJ. This suggests that the pelvis rotated as a ‘ring’ and was not capable of intra-pelvic motion. This is consistent with your prior finding that the left SIJ was ‘locked’ and unable to move and biologically plausible. While we expect an IPT to occur in congruence with a TPR, it won’t if the SIJ is not able to move.

Diane’s comment following Jo’s comments in this second version of the case report:

In this second version of the case report, you noted above that one SIJ was actually unlocked in quiet standing (likely the right given what you report below). Therefore, I suggest that the right SIJ was already unlocked prior to this squat task, which would eliminate the hypothesis that an IPT was occurring in the squat task. If the right SIJ was already unlocked, you wouldn’t feel anything occur within the pelvis (intra-pelvic) other than the TPR (rotation of the entire pelvic ring) and this could leave the impression that the SIJ was ‘locked’, when in fact the right side was ‘unlocked’.

Jo’s response:

That makes a lot of sense – thank you.

- Knees and Feet: No change.

TIMING: Thorax fails first.

Finding Drivers in the Squat Task:

- Correcting the CSp induced a LTPR of the lumbar spine segments at L4 and L3.

- Correcting the left hip improved the LTPR of the pelvis but increased the 2nd thoracic ring translation left/rotation right and the RTPR of the low thorax.

- Correcting the right calcaneus (foot) made the thorax worse.

- Correcting the left hip and the 7th thoracic ring improved the alignment at all other sites.

Outcome: Co-Driver thorax (7th thoracic ring) and left hip.

Weight transfer in standing

- Cranium & CSp: No change from Quiet Standing.

- Thorax: During a weight-transfer to the right leg the alignment of the 5th and 7th thoracic rings improved, however the alignment of the 2nd and 9th thoracic rings remained the same.

- LPHC: transferring body weight to the right leg, the right sacroiliac joint unlocked and the lumbar spine increased side-flexion to the left. No change at the left hip.

- Knees and Feet: No change.

TIMING: Thorax failed first.

Finding Drivers in the Weight transfer task in standing:

- Correcting the cranium and CSp resulted in no change in the alignment of any other site of FLT.

- Correcting the left hip resulted in slight improvement in the alignment of the thoracic rings.

- Correcting the pelvis made the alignment of the thorax worse and also resulted in more left side-flexion of the CSp.

- Correcting the left hip and the 7th thoracic ring improved the alignment of all sites of FLT during this task.

Outcome: Co-Driver thorax (7th thoracic ring )and left hip.

Deadlifts (10kg – bar only)

- Cranium & CSp: FLT previously reported in Quiet Standing (QS) remain the same throughout the movement.

- Thorax: tension in the left shoulder is increased when holding the bar (assuming the start position for this exercise) and increases the sub-optimal alignment previously reported in QS in the left shoulder girdle to cranium. The alignment of the 2nd and 5th thoracic rings improved on descending then worsened on ascending, the 7th thoracic ring remained the same throughout the task, and the 9th thoracic ring improved throughout the task.

Diane’s question:

This is an interesting finding i.e. the 2nd and 5th thoracic ring alignment improved on the descent and worsened on the ascent. What neuromuscular vectors could explain this finding?

Jo’s response:

Passively, Mr B is ‘locked’ in heel strike phase of gait on the left, which would suggest the following biomechanics are ‘locked’ in to his system; sacrum TPR [L] relative to midline, left innominate posteriorly rotated relative to sacrum, TPR of the lumbar spine to the [L] with lateral flexion [R] (compressed R). When weight-bearing, Mr B. unlocks on the [R] SIJ. The only thing different about this task is the added weight: 10kg Barbell which influenced observations of 2nd and 5th thoracic ring alignment improving in descending squat, but not in ascending. To note: In Quiet Standing I noted bilateral FLT’s of the shoulder girdles; left humeral head and scapula medial border winging; right scapula is downwardly rotated and right clavicle is anteriorly rotated. But failed to monitor them during this modified task. Maybe, the barbell provided positional awareness of the upper thorax incongruencies, allowing Mr. B. to improve the alignment of the shoulder girdles which may have influenced the alignment of the 2nd and 5th thoracic rings (serratus anterior). And/or with this higher load task (10kg dumbbell) the added load may have also influenced the set-up of this task for Mr. B. With descending being supported by momentum and reduced ground reaction forces as the body off-loads, this reduced demand phase of the squat may have provided Mr. B having the opportunity to create feed forwards of the deep segmental muscles which may have contributed to control of 2nd and 5th thoracic rings. Maybe this was all lost in the ascending phase of the squat due to increased demands of the task (now working against gravity, higher ground reaction forces, increased load) created a concern cognitively, but may have also contributed to over-activity of the superficial muscles and therefore reducing the likelihood of segmental lumbar control.

Diane’s followup:

Great answers if the question pertained to strategy and motor control! I was thinking of something much more simple! The weight load is higher ascending for sure, so motor control and strength/capacity could be a biologically plausible explanation for the alignment of the thorax worsening on ascension from the squat and improving on descent. I was thinking of vectors influenced by hip position. If the 2nd and 5th thoracic rings were compensating for the 7th and 9th in this task, another mechanism could be the influence of any vectors from the psoas/diaphragm influencing the ascent. If the hip flexors failed to eccentrically lengthen in a timely manner and created asymmetric vectors of force on the lower thoracic rings (7 and 9), then this influence would appear on ascent and disappear on descent. This mechanism is plausible given that you note the left hip is a driver in the squat task. The 2nd and 5th thoracic ring findings may then be compensatory for the 7th and 9th.

- LPHC: as centre of mass (COM) is taken over the toes left femoral head externally rotated), right SIJ FLT (unlocks) (Diane’s comment – this finding suggests that the right SIJ was NOT unlocked in QS!) and L5 posteriorly translated) with a TPR [R]).

- Knees and Feet: No change.

TIMING: Hip fails first, shortly followed by thorax.

Finding Drivers during Deadlifts:

- Correcting the right calcaneus made the thorax worse.

- Correcting the left hip and the 7th thoracic ring improved all sites of FLT.

Outcome: Co-Driver thorax (7th thoracic ring) and left hip.

Summary of Findings

Conclusion from the assessment of multiple screening tasks related to Mr. B’s meaningful tasks is that the 7th thoracic ring and the left hip are co-drivers for multiple tasks and require further analysis to determine the underlying system impairments.

At this time, we both agreed deadlifts may add further complications or consolidate reported FLT and therefore should be removed from Mr B.’s daily regime.

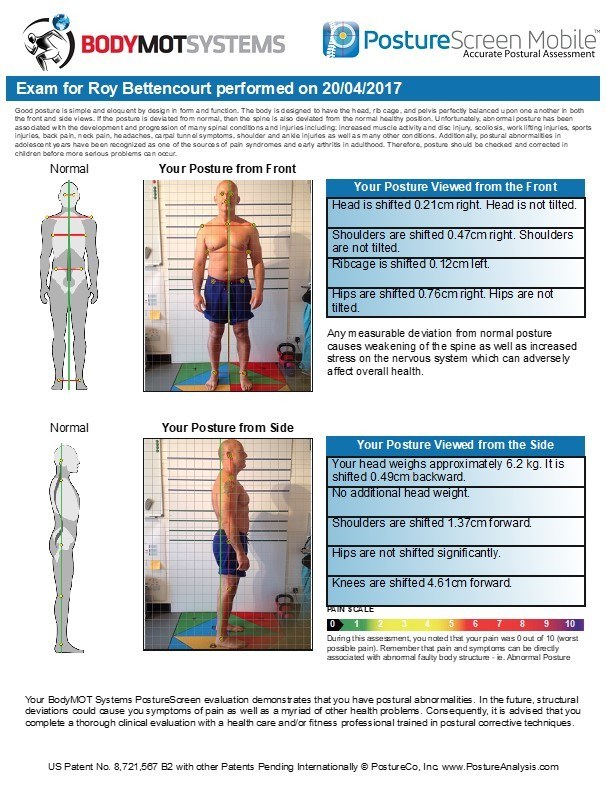

Posture Analysis

Conclusion from the assessment of multiple screening tasks related to Mr. B’s meaningful tasks is that the 7th thoracic ring and the left hip are co-drivers for multiple tasks and require further analysis to determine the underlying system impairments.

At this time, we both agreed deadlifts may add further complications or consolidate reported FLT and therefore should be removed from Mr B.’s daily regime.

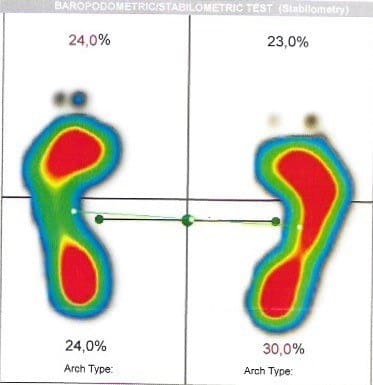

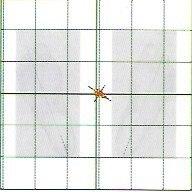

Pressure Plate – 30 second Quiet Standing data capture.

- Mr B. distributes body weight unevenly with 48% on the left and 52% on the right. Previous studies have correlated weight distribution with optimal lumbopelvic hip biomechanics generally has a 0.5% difference between left and right with no correlation with handedness or footedness. Therefore, this data suggests that Mr B. in quiet standing loads his right-side 1.5% more than a person who has optimal lumbopelvic hip biomechanics.

- This data also suggests Mr B.’s centre of mass (COM) is slightly deviated in a transverse plane rotation to the right by 32.27 degrees. No data to date has been collected on COM optimal position.

- The ‘Arch Type’ pressure distribution (red for highest loaded points) correlates with the manual screening of the foot mechanics.

Further Assessment of Drivers

Diane’s comment:

In the ISM approach, further assessment is done on the regions of the drivers. An ISM heading for this section would be….. Further Assessment of the Drivers (Thorax (specifically the 7th thoracic ring) and the left hip). Then you could look at the relationship between these two impairments AND the resultant findings of the pelvis in supine to see ‘who is influencing who’. That would be an ISM approach. How does the title here (previous title was Supine Passive Assessments) fit into your assessment?

Jo’s response:

I explore passive gait biomechanics in all subjects – I believe it allows an understanding of how they are ‘set-up’ before adding other challenges to the system i.e. weight bearing or movement tasks. This gives me an opportunity to explore other explanations to ‘why’ their systems fail when adding other factors. Hopefully in my explanation above (page 19 re. 2nd and 5th thoracic ring biomechanics during deadlift) may help ‘why’ I add these to my assessment.

Diane’s comment:

So many things are different in supine compared to standing, I wouldn’t be surprised if Mr. B’s findings were, on occasion, different between task positions and thus confuse the clinical picture unless the underlying system impairment was articular or myofascial – these vectors don’t necessarily change with position. Visceral and neural system impairments can change from position to position and thus change findings.

Gait Biomechanics

On his left-side Mr. B. is locked in weight acceptance task of gait causing an estimated 14mm vertical loss from the normal path of the body centre of mass (COM).

Vector Analysis of the Co-driver (7th thoracic ring and left hip)

Thorax

Neural system impairment of the thorax: Passive listening after correction release of the 7th thoracic ring (in standing) revealed an initial long anterior inferomedial vector on the left suggesting the left external oblique. After release of this superficial vector a second correct, release, and listen (passive listening) revealed a deeper neuromuscular vector from the diaphragm.

Jo’s comment:

During dissection, when I peel away the IO, the vertical fibres of the TA and IO meet on the inside of the ribcage under the fascia of the diaphragm. This is what my hands were feeling on this day, with this patient. It was this thickening at this location I was describing. This vector was short, quick, deep, ‘sucking in’ and ‘bundling’ of tissue.

Left Hip

Neural system impairment of the left hip: functional range of motion (amplitude of possible movement with a centered femoral head) was determined to be minus 30 degrees of extension. Vector analysis of the left hip (center the femoral head, release and listen) identified a vector of force from the left iliacus. The passive listening on release of the hip correction in supine revealed a vector that externally rotated the femur and this vector pulled the femoral head superior above the inguinal ligament.

Applied Kinesiology to triangulate findings to date

- Left external oblique – no neural lock, suggesting adaptive shortened

- Left iliacus – no neural lock, suggesting adaptive shortened

- Left serratus anterior – searching, suggesting stretch weakened – not a dominant vector so not treating.

Diane’s comment:

Cool Correction!

Further Assessment of Multifidus and Abdominal Wall

- supine position;

- Left EO inability to recruit

Diane’s comment:

but the dominant vector impairing the 7th thoracic ring was from left EO which suggests it is over-active, therefore; maybe the inability to recruit on this test is because it is already on?

Jo’s response:

That is correct.

-

- Left IO overactive

- TA optimal (Rest, Recruit, Relax)

- Right erector spinae and EO inability to recruit

Diane’s comment:

Did you happen to note if any of this changed with correction of the 7th thoracic ring and/or left hip position in supine? Often with persistent recurrent LBP segmental multifidus is inhibited and atrophied. Did you assess his segmental multifidus and its response to correcting the 7th thoracic ring?

Jo’s response:

I did not look at this Diane. A complete oversight. However, I do appreciate how much I would have learnt by doing this. NOTE TO SELF. Thank you.

Introduction to how I believe non-optimal muscle vectors should be approached

Muscle Physiology (Muscle States)

Treatment for me has been about trying to understand the biomechanical adaptions of the vectors during compensatory phases i.e. primary, secondary, and tertiary if not identified early. The following is part of a literature review I have been chipping away at over the past seven years. Maintained length-associated mechanical property changes in muscle is a major cause of movement impairments: Adaptive Shortened (AS) and Stretch Weakened (SW) (Alder, Crawford, & Edwards, 1959; Baker & Hall-Craggs, 1978; Booth & Kelso, 1973; Cailliet, 1977; Crawford, 1973; D. F. Goldspink, 1976, 1977a, 1977b; G. Goldspink, Tabary, Tabary, Tardieu, & Tardieu, 1974; Gossman, Sahrmann, & Rose, 1982; Griffin, Anderson, & Passos, 1971; Herbert, 1988; Janda, 1983; Morrissey, 1989; Sahrmann, 1987; Smidt & Rogers, 1982; Sohar, Takacs, & Guba, 1977; Tabary, Tabary, Tardieu, Tardieu, & Goldspink, 1972; A. Tardieu, Vachette, Gulik, & le Maire, 1981; C. Tardieu, Colbeau-Justin, Bret, Lespargot, & Tardieu, 1981; G. Tardieu, Tabary, Tardieu, & Tabary, 1973; G. Tardieu, Tabary, Tardieu, Tabary, et al., 1973; G. Tardieu & Tardieu, 1987; P. Williams, Watt, Bicik, & Goldspink, 1986; P. E. Williams & Goldspink, 1978, 1981, 1984). Based on this knowledge, my treatment plan was as follows:

So far from my Muscle State Literature Review I have been able to identify the following phases of muscle physiology change if the muscle is behaving in an Adaptive Shortened (AS) position;

DAY 1>3 becomes hypertonic

- < ROM

- < Elasticity

- > Connective tissue in perimysium

- > Hydroxyproline

- > Malalignment of joints – Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition (AMI)

If there has been no intervention then the muscle state progresses.

DAY 4 TO 3 WEEKS becomes atonic

- > Weakness

- > Catabolism

- > Thickness in muscle (10>15 fascicles for each GTO)

- > Remodelling of perimysium and endomysium

- > AMI

- < Loss of sarcomeres in Adults

- < Reduction of sarcomeres in the young

- Inhibition of Sherrington’s Law

- Breakdown of proteins

- Steeper and earlier passive and peak tension curve

Again, if there has been no intervention during this period, the muscle adapts again and remains in the state below until identified and treated correctly.

After 3 WEEKS > becomes weak, short, and tight

- > 35% denervation

- > Thickness

- > Catabolism

Janda (1990) demonstrated passive stretching of any muscle in adaptive shortened (AS) state would have adverse reactions. However, based on the science, by day 4 an AS muscle does not have the ability to contract (due to the catabolic enzyme being released) therefore Reciprocal Inhibition (R.I.) would be used as a tool to support releasing an AS muscle if the antagonist muscle can be isolated. I tend to get the Patient to think about the antagonist muscle shortening whilst feeling primary muscle lengthen. A form of Muscle Energy Technique (MET). If the antagonist cannot be isolated then I will assist with another form of MET of the agonist and treat with ‘pin and stretch’ technique at the Musculotendinous Junction (MTJ) to stimulate GTO mechanism to stimulate relaxation in the AS muscle. Soft tissue work of the AS muscle would be to bring distal to proximal fascicles together in the action of a ‘PINCH’ applying between 1>7KG of force downwards and drawing together. The whole process of treatment is to increase ROM in the muscle and to begin to reverse the physiology.

Within 14 days of the AS muscle being mobilised the muscle protein increases, 60 days after mobilisation and the ATP and glycogen increases in the AS muscle. After 120 days of mobilisation the tension curve is corrected. The timelines given above are based on using one of the techniques I previously mentioned. A combination of all techniques has never been tested and therefore the timeline for improvement remains unknown. However, if AS remains present after treatment, within the discipline of Applied Kinesiology, a consistent finding of an AS muscle has also been associated with the following organs; Thymus (immune), Stomach (inflammation), and Adrenals (fight or flight) and therefore the driver of AS muscle adaption may be nutritional deficits on the following organs; adrenals, thymus, or stomach.

Initial Treatment (RACM)

Release & Align

The left External Oblique (related to the 7th thoracic ring diver) and left iliacus (related to the left hip driver) were treated as follows;

- Left EO – unable to reciprocally inhibit using the right multifidus and/or the right EO so treated left EO with hands-on Pin and Stretch MET technique,

The focus on breath (interdigitating with psoas to diaphragm’s medial arcuate ligament) during the left EO treatment (MET pin and stretch) was combining the neural and the short, quick, deep, ‘sucking in’ and ‘bundling’ of tissue – I just felt like we needed more space in this area and breathing felt like the right thing to add to this release.

Diane’s comment:

Not sure I understand that sentence. Fair to say this?

When palpating the tissue in this area it felt restricted, shortened, and compressed. Therefore, during the release technique, I emphasised for Mr. B. to visualise opening this area, to breathe some space into this area as I applied the soft tissue work.

In addition to the neural system releases, Mr. B was advised to inhale/exhale during this release technique to address the deeper myofascial component of the restriction.

Jo’s response:

Yes, completely.

- Left iliacus – Reciprocal inhibition using Gluteus maximus, followed by applying the PINCH technique with my right hand located superficially on the left innominate and my left hand on the lesser trochanter whilst using the femur as the lever and my chest to create the movement required to PINCH.

Diane’s comment:

What was the response with respect to the alignment of the 7th thoracic ring and the left hip after these two release techniques?

Jo’s response:

Ah, yes. Reassessment of the vectors by triangulating; listening; Applied Kinesiology; and passive assessment of gait (I did not want to re-test any of the weight bearing tasks at this point as I did not feel his system would be able to keep the gains we had made) all assessments agreed these neural drivers were no longer present.

Diane’s comment/question:

I think this means that the 7th thoracic ring was in better alignment and the left femoral head was more centered after your treatment, yes?

Jo’s response:

Agreed.

Assessment of Mr. B. multifidus and abdominal wall post-treatment

- supine position;

- Left EO able to initiate recruitment

- Left IO dampening down of recruitment

- TA optimal RRR (rest, recruit, relax)

- With education and instruction was then able to recruit right multifidus

- Right EO able to initiate recruitment with no training.

Connect & Move

Once Mr. B. was able to visualise opening the lower thorax and use his breath to create more space here, I asked him to move his knees to the right.

Diane’s question:

was there any attention paid to correcting the alignment of the 7th thoracic ring during this technique?

Jo’s response:

Yes, I had my hands on his thorax and was checking for any FLT’s;

- Part 1: In supine, knees bent, I asked Mr. B. to take a deep breath in and think about lengthening the left side of his waist. At the same time, the 7th thoracic ring (left side) and left femoral head was palpated. As he breathed in, he was instructed to create space and length between the two palpation points (7th thoracic ring and left hip). His immediate response to this cue was to laterally flex his spine to the right, in other words, he tried to ‘do something’ as opposed to ‘stop doing something’. Considerable training and focus was required for him to learn to let something go as opposed to do something.

- Part 2: I then asked him to hold his breath and slowly lower his knees to the right – again focusing on length and breath

Diane’s comment:

how can he focus on breath if you have him holding it?

Jo’s response:

Jo’s response: LOL. Breath as the rhythm i.e. hold breath – slowly lower knees to right, breathe out when returning the knees to midline. Mr. B. demonstrated an inappropriate motor pattern during the initial stages of this movement; he would hip hitch (sidebend) on the left then start to roll his knees to the right. We spent time bringing his awareness to this sub-optimal pattern (my hands-on, to hands-off) followed by de-training the movement by reiterating the initial movement he needed to keep the length he had gained on inhalation whilst he rolled the knees to the right. The lengthening and position was held for 3-5 seconds.

- Part 3: On the exhalation, the movement was to bring the knees back to the midline position without sidebending on the left and to focus on the movement from the knees being a ‘pelvic roll to the left’ rather than a sidebend.

Diane’s comment:

It appears no connect cue is required here since you state that TrA in supine is optimal and there is over-activation of the superficial system only. There is no mention of the behaviour of dmf with or without correction of either driver. That would be of great interest to me with this story. Why would this interest me?

Jo’s response:

because it is plausible to suggest the behaviour of dmf may have been caused by the 7th thoracic ring and left hip but most importantly this may conclude why he has chronic low back pain.

Diane’s comment:

Exactly! Whenever you have a client with recurrent low back pain, remember Hides & Hodges individual and collective research on deep multifidus – it almost always is a factor in segmental lumbar control during loading. The deep segmental fibres of multifidus have been shown to be inhibited within 24 – 48 hours of an acute injury and recovery is not spontaneous for most.

Home Exercise Plan

The following therapeutic exercises were recommended for Mr. B on 03/28/2017. All Corrective Exercise Prescriptions are online with interactive videos demonstrating the application of the exercise.

No equipment is recommended for this program.

Diane’s comment:

While this may not be available, I still would have liked more information about his lumbar segmental multifidus. Given his history and lack of segmental control, this is a key ISM piece as is the relationship of correcting the 7th thoracic ring on restoring segmental motor control. You mention below that you gave him a cue to connect to the right dmf (no segment mentioned but I suspect it related to the L4-5 hinge previously noted) but I didn’t see any segmental assessment, nor does it mention which segment of dmf you assessed, nor the specific cue given (Part 1 Series).

Jo’s response:

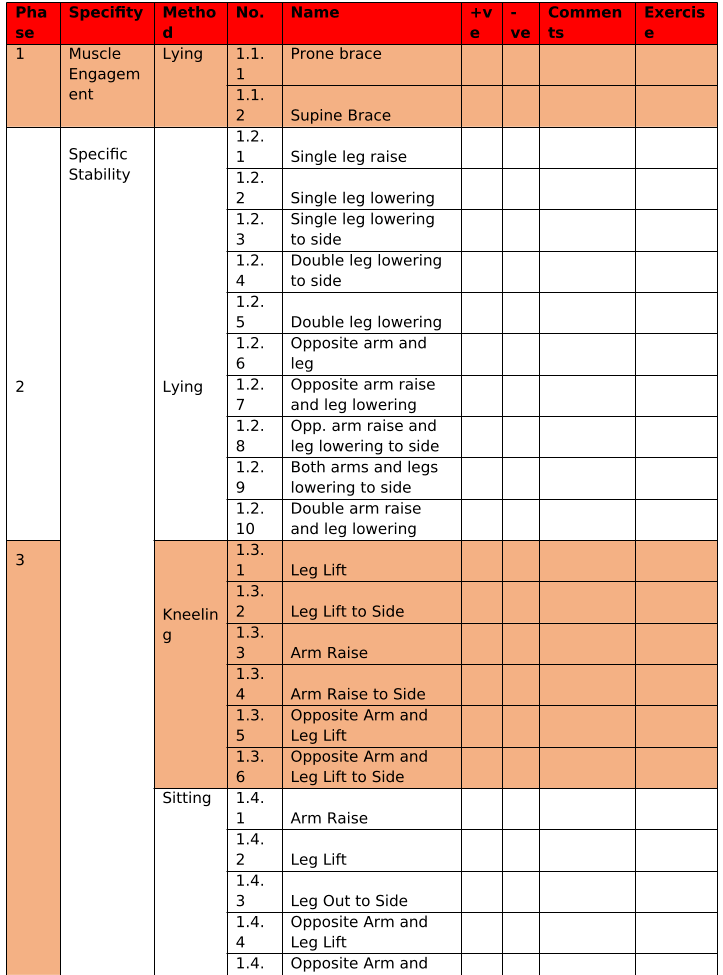

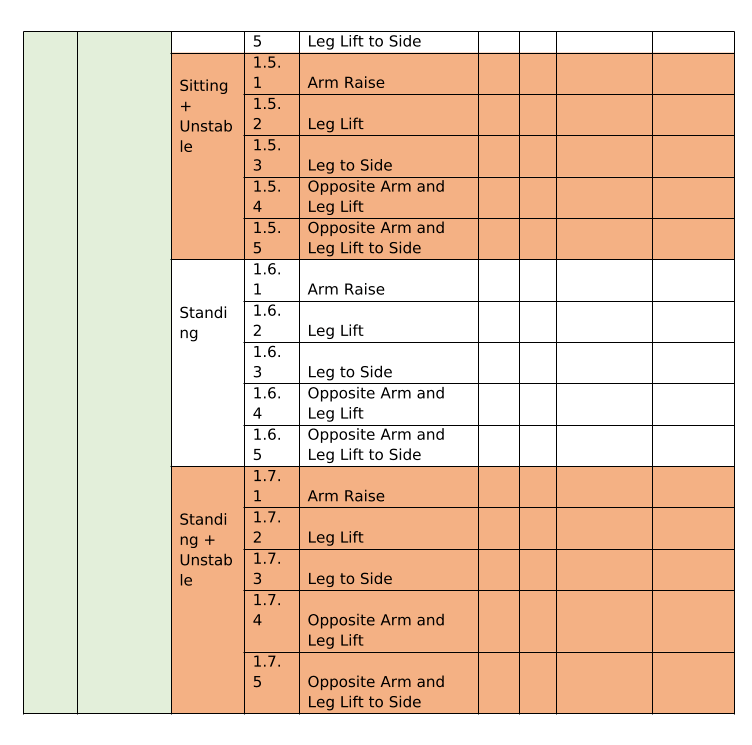

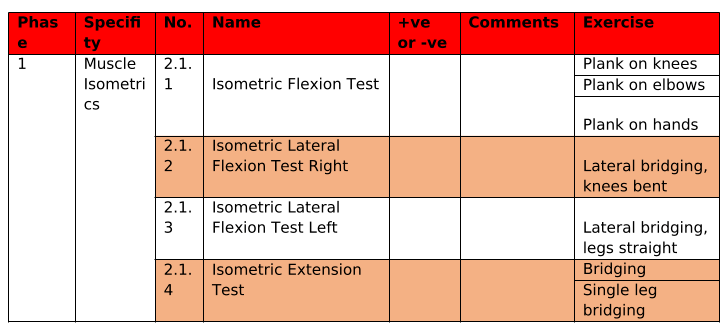

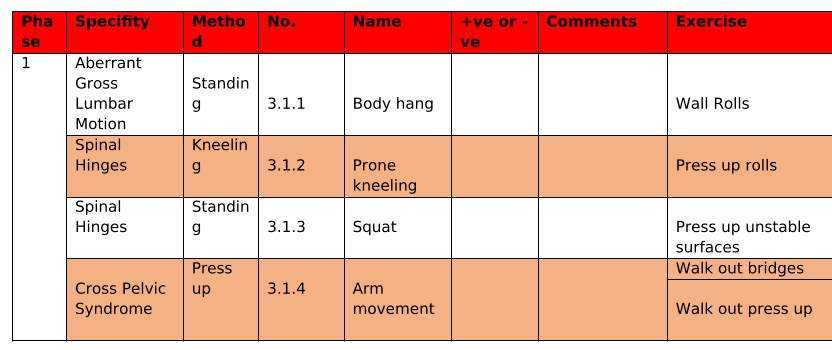

I use Professor Stuart McGill’s protocol of stability for the trunk. I have attached the document below. The exercises are the assessments and the corrective exercises. The protocol is to palpate recruitment at each phase/exercise. When they are not able to optimise on the exercise, they are given the two-exercises before the one they were not able to achieve and the one they struggled with. For example: Mr B. was not able to optimally perform 1.2.1 on the post treatment visit (the appointment we are discussing above) so his homework was to complete 1.1.1 3 sets of 10 reps, 1.1.2. 3 sets of 10 reps, and 1.2.1. 3 sets of 5 reps: all with the awareness of breath and position as written above. Each appointment this is part of the assessment process for homework.

Diane’s comment:

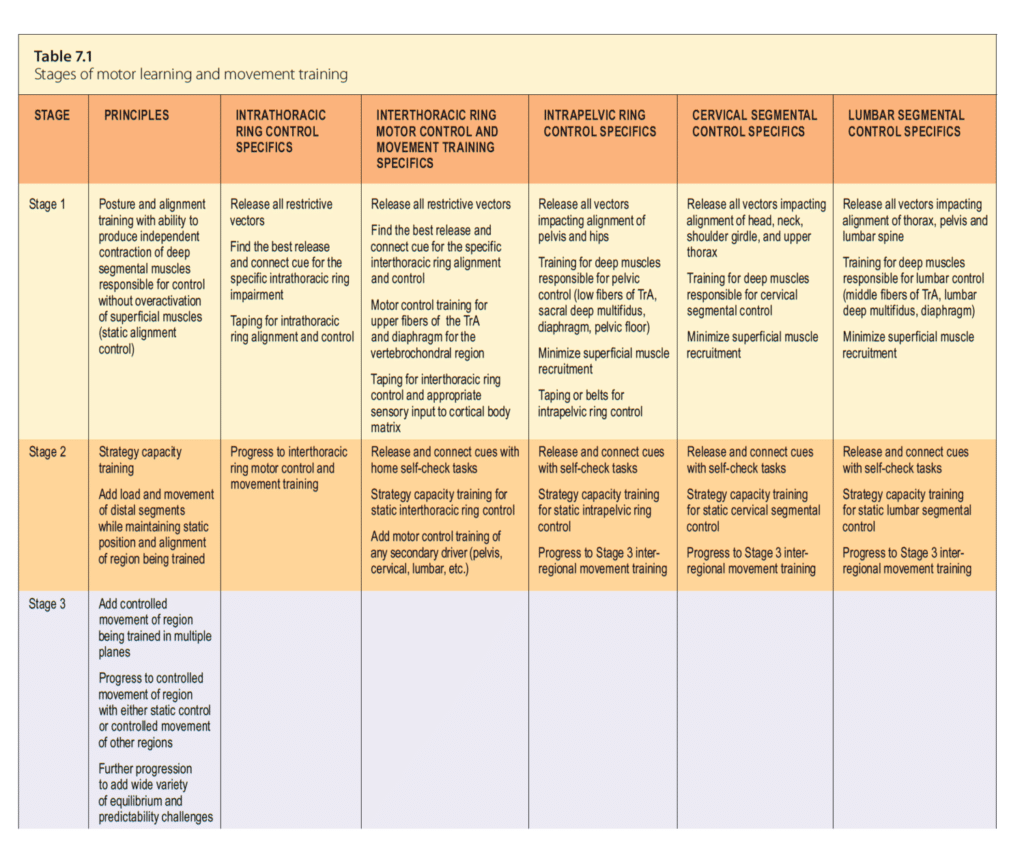

To me, these exercises are Stage 2 capacity training of a strategy, the exercises don’t change strategy or specifically target one ‘offline’ muscle. Stage 1 motor control training is about training the brain’s recruitment patterns of individual muscles and then to build motor patterns prior to training capacity (strength/endurance). This is a key difference between the McGill protocol and a motor control training protocol. If Mr. B’s deep segmental multifidus was not being recruited automatically, then these exercises would not automatically ‘bring it back online’ or wake it up. Maybe there is more contained in the Phase 1 stage – prone brace, supine brace in the chart below. The principles of what you have presented appear the same other than the motor control training part. This is a principle difference between motor learning training and McGill’s protocol for ‘core training’ and a long debated topic between McGill and Hodges. There is a place for both.

Here is a table from the Thorax book (The Thorax – An Integrated Approach – Handspring Publishing 2018) on motor learning and movement training and the stages for each.

Stabilise Screening and Corrective Exercises

STEP 1 – Muscle Engagement & Specific Stability

STEP 2 – Muscle Isometric Screening & Specific Stability

STEP 3 – Functional Stability Screening

Jo’s response:

Both exercises were instructed with the left EO and and right dmf connect to then move. However, having reviewed this Case Study again I now agree the Glute Bridge March would have been too much load at this stage for Mr. B. and maybe supine and standing recruitment of the left EO and right dmf would have been a better progression for his homework.

Diane’s question:

When you were finding drivers, you noted that correcting the 7th thoracic ring and the left hip restored ‘all other sites of FLT’ so I’m assuming that meant these corrections restored control of the right SIJ. But how?

Jo’s response:

These findings suggest it may well have been the right-side iliocostalis (7th thoracic ring fascicle to [R] SIJ) that contributed to the FLT.

Diane’s comments:

Often, changing alignment of the trunk (e.g. 7th thoracic ring and left hip) changes recruitment strategies. One thing ISM helps explain is the relationship between twists in the trunk and motor control strategies. So far, I think I understand that his abdominal wall was over-active but TrA was optimal – so something is causing the loss of segmental lumbar control – likely multifidus. Palpation of the recruitment of dmf at the lumbar and sacral levels with and without the 7th thoracic ring correction would have provided further information to determine if the 7th thoracic ring was a player here and whether a specific connect cue for multifidus was needed. If you didn’t do this, let me know and I’ll frame some hypothetical questions around this topic for the next version.

Jo’s response:

I didn’t do this Diane, and am kicking myself – when you state these things it seems to obvious…

Diane’s comment:

LOL – it’s just about learning – not about kicking ourselves!

Follow-up treatment sessions

21st April 2017

- Subjective response to previous session:

- Been exploring movement on a day-to-day basis and trying to understand the effect of poor biomechanics

Diane’s comment:

this brings awareness that different strategies have on biomechanics is a huge part of patient learning and neuroplasticity.

-

- Remains signed-off from work.

- Been completing homework as prescribed.

Diane’s comment:

compliance is essential for a good prognosis (massed practice with focused attention)

- Meaningful complaints:

- Weakness in low back during standing feels worrying, although when walking Mr B remains cautious and concerned.

Diane’s interpretation:

he still doesn’t feel ‘safe’, therefore his strategies will still be ‘braceful’ and protective.

-

- Tightness in ribs and low back on the left when squatting (toilet or sitting) has now gone.

- No longer has the ‘ripping’ sensation anterior right thigh.

- Objective findings: Meaningful Task; Squatting.

- No longer passively ‘locked’ in any specific phase of gait.

- Optimal loading through the pelvis and hip joints.

- Driver: Left shoulder/shoulder girdle.

- Vector analysis of the new driver:

- Adaptive shorted left sternal fibres of pectoralis major, left serratus anterior

- Treatment:

- Release/align: Release both muscles with AS treatment and provide home self-release techniques. Post release, roll the humeral head/shoulder girdle in a forwards, up, back, down motion and hold in the aligned position for 5 seconds. Bring your awareness to how this now feels.

- Connect/control & move: to think of space in the anterior shoulder joint, opening up the chest, when you feel this new position is set, start with arm frontal raise keeping this new position.

19th May 2017

- Subjective response to previous session:

- Low back feeling strong and non-restrictive whilst asymptomatic.

- Right anterior thigh remains free from the tearing symptoms.

- If doing any strenuous activity bilateral thighs fatigue.

- B. was signed back to work on Limited Duties and Fire Fighter Specific

- Meaningful complaints:

- Remains concerned on how his body will cope putting on all fire kit breathing apparatus (BA)

- Subjective findings: Meaningful Task; putting on and wearing full fire kit (clothing, helmet and breathing apparatus (BA) Kit) note: BA Kit weighs 15kg, whilst the helmet weighs 1.2kg.

- Change in symptoms while wearing BA Kit

- Low back: feels tight and weak

- Neck: tight and restricted on the right with rotation to the right.

- Change in symptoms while wearing BA Kit

- Objective findings: Meaningful Task standing in full fire kit;

- Cranium & Cervical spine:

- Wearing fireproof clothing only: cervical spine side-bent to the left, 2nd and 3rd cervical vertebrae translated right/rotated to the left congruent with the cranium (trousers have braces over the shoulders).

- Addition of BA Kit and helmet: all of the findings noted above worsen when helmet is put on – which is put on after BA kit.

- Thorax:

- Wearing fire proof clothing only: nothing to report.

- Addition of BA kit and helmet: 2nd thoracic ring translated to the left/rotated to the right which is incongruent with the craniovertebral findings, and 8th thoracic ring translated to the right/rotated to the left.

- Shoulder girdle:

- Wearing fire proof clothing only: Right scapula downwardly rotated.

- Addition of BA kit and helmet: right scapula gets worse when BA kit is put on, remains the same when helmet is worn.

- LPHC:

- Wearing fire proof clothing only: quiet standing and weight transfer, nothing to report.

- Addition of BA kit and helmet: nothing to report in quiet standing, however in weight transfer on to the right-leg in standing and the right SIJ unlocks. No change when helmet is added.

- Knees:

- Wearing fire proof clothing only: Unremarkable

- Addition of BA kit and helmet: Unremarkable.

- Feet:

- Wearing fire proof clothing only: Unremarkable

- Addition of BA kit and helmet: Right calcaneus and forefoot inversion gets worse when BA kit is put on. No change when helmet is put on.

- Cranium & Cervical spine:

Mr B. remained in his fire proof clothing and helmet whilst the timing of the site specific FLT was investigated when adding the 15kg BA kit. My reasoning for this was due to the fact that the non-optimal biomechanics were made worse mostly when adding the extra weight of the BA kit.

TIMING: Thorax fails first when BA Kit is put on, then right foot.

When correcting the 2nd thoracic ring the right scapula and craniovertebral alignment was made worse and the right SIJ remained to unlock in standing weight transfer. When correcting the right calcaneus, the craniovertebral alignment was made worse and the right SIJ remained to unlock in standing weight transfer. When correcting the 8th thoracic ring no improvements were found. When correcting the craniovertebral alignment, the right scapula alignment and 2nd thoracic ring corrected whilst the right SIJ no longer unlocked during standing weight transfer on to the right leg. Unable to get an accurate analysis of the calcaneus.

Diane’s comment:

The cranium and upper neck had already failed when the fireproof clothing was added whereas the thorax didn’t fail with the clothing addition but rather the addition of the BA kit. Therefore, the first site to fail was actually the cranial region and not the thorax. This is consistent with the results from your site correction findings – correcting the cranial region resulted in best improvement in other sites of failed load transfer.

- Vector analysis of the driver – cranial region: left levator scapula

- Treatment:

- Release/align: dry needing release for the left levator scapula. Complete some easy levator scapula stretches for 2 weeks. Try to remain long through the neck and have some lightness (weight) through the upper chest hold the aligned position whilst putting on your fire proof clothing, BA kit and helmet. Bring your awareness to how this now feels.

- Connect/control & move: think of ‘space’ in the posterior left side of your neck, imagine there is a water balloon between your shoulder and neck – stand tall and be proud. When you feel this new position is set, start with light left arm scapula protraction exercises.

9th June 2017

Subjective response to previous session: Meaningful complaint:

- Asymptomatic since last appointment and has resumed normal ADL tasks effortlessly.

Objective assessment: Meaningful tasks for work

- Completion of Functional FireFit Assessments: Hose and Ladder Drills, BA Drills, Mannequin Drills, and embussing and debussing the Fire Engine all with optimal biomechanics.

- Signed back to Full Operational Duties.

Jo’s comments on doing this case report:

This Case Study was a great opportunity to learn from failure.

Completing this case study, with personal mentoring from Diane Lee, has given me access to debating, discussing, and understanding biomechanics in musculoskeletal practice – not just research. I have been able to collate eight years of research into a case study narrative with a highly respected professional of Manual Therapy – one of the rare professionals I have trained with who has debatable values and a growth mindset, giving me the space to share, learn and develop together.

This journey created synergy between two disciplines encouraging values highlighted by Prof. Caroline Finch regarding what is needed to progress MSK research and practice:

“Future advances in sports injury prevention will only be achieved if research efforts are directed towards understanding the implementation context for injury prevention, as well as continuing to build the evidence base for their efficacy and effectiveness of interventions”

I have been able to reflect on my failures – in a safe space – and progress my scientific research from purely academic to practical skills supporting patient’s wellbeing. Failure within Manual Therapy is not about lack of skill, knowledge, or understanding, it is about the inevitabilities of failure when dealing with complex systems, such that is the human body. When the probability of error is high, such as in complex systems, there is more scope for error and thus the importance of learning from failure becomes more essential, not less.

Finally, my reasons for choosing this particular Case Study were based on the fact I had already seen this gentleman previously for the same symptoms, and I was keen to test my new skills (ISM Clinical Mentoring) integrated with my research to see what I missed in previous appointments with this gentleman. This journey of skill development and hypothetical deductive reasoning has been quite extraordinary.

Diane’s comment:

Thank you Jo – I learned a ton as well working with you on this report!

References

Alder, A. B., Crawford, G. N., & Edwards, R. G. (1959). The effect of limitation of movement on longitudinal muscle growth. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 150, 554-562.

Baker, J. H., & Hall-Craggs, E. C. (1978). Changes in length of sarcomeres following tenotomy of the rat soleus muscle. Anat Rec, 192(1), 55-58. doi:10.1002/ar.1091920105

Booth, F. W., & Kelso, J. R. (1973). Production of rat muscle atrophy by cast fixation. J Appl Physiol, 34(3), 404-406.

Cailliet, R. (1977). Soft Tissue Pain and Disability (3 ed.). USA: F. A. Davis.

Crawford, G. N. (1973). The growth of striated muscle immobilized in extension. J Anat, 114(Pt 2), 165-183.

Goldspink, D. F. (1976). Changes in size and protein turnover of skeletal muscle after immobilization at different lengths [proceedings]. J Physiol, 263(2), 269P-270P.

Goldspink, D. F. (1977a). The influence of denervation and stretch on the size and protein turnover of rat skeletal muscle [proceedings]. J Physiol, 269(1), 87P-88P.

Goldspink, D. F. (1977b). The influence of immobilization and stretch on protein turnover of rat skeletal muscle. J Physiol, 264(1), 267-282.

Goldspink, G., Tabary, C., Tabary, J. C., Tardieu, C., & Tardieu, G. (1974). Effect of denervation on the adaptation of sarcomere number and muscle extensibility to the functional length of the muscle. J Physiol, 236(3), 733-742.

Gossman, M. R., Sahrmann, S. A., & Rose, S. J. (1982). Review of length-associated changes in muscle- experimental evidence and clinical implications. Physical Therapy, 62(12), 6.

Griffin, W., Anderson, S. J., & Passos, J. Y. (1971). Group exercise for patients with limited motion. Am J Nurs, 71(9), 1742-1743.

Herbert, R. (1988). The passive mechanical properties of muscle and their adaptions to altered patterns of use. The Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 34(3), 5.

Janda, V. (1983). On the concept of postural muscles and posture in man. Aust J Physiother, 29(3), 83-84. doi:10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60665-6

Morrissey, M. C. (1989). Reflex inhibition of thigh muscles in knee injury. Causes and treatment. Sports Med, 7(4), 263-276.

Perry, J. (1992). Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function. NJ: Slack Incorporated.

Sahrmann, S. (1987). Muscle imbalances in the orthopaedic and neurologic patient. Paper presented at the Proceedings of 10th International Congress of the World Confederation for Physical Therapy, Sydney.

Smidt, G. L., & Rogers, M. W. (1982). Factors Contributing to the Regulation and Clinical Assessment of Muscular Strength. Physical Therapy, 62, 5.

Snodgrass, S. J., Heneghan, N. R., Tsao, H., Stanwell, P. T., Rivett, D. A., & Van Vliet, P. M. (2014). Recognising neuroplasticity in musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a basis for greater collaboration between musculoskeletal and neurological physiotherapists. Man Ther, 19(6), 614-617. doi:10.1016/j.math.2014.01.006

Sohar, I., Takacs, O., & Guba, F. (1977). The influence of immobilization on soluble proteins of muscle. Acta Biol Med Ger, 36(11-12), 1621-1624.

Tabary, J. C., Tabary, C., Tardieu, C., Tardieu, G., & Goldspink, G. (1972). Physiological and structural changes in the cat’s soleus muscle due to immobilization at different lengths by plaster casts. J Physiol, 224(1), 231-244.

Tardieu, A., Vachette, P., Gulik, A., & le Maire, M. (1981). Biological macromolecules in solvents of variable density: characterization by sedimentation equilibrium, densimetry, and X-ray forward scattering and an application to the 50S ribosomal subunit from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry, 20(15), 4399-4406.

Tardieu, C., Colbeau-Justin, P., Bret, M. D., Lespargot, A., & Tardieu, G. (1981). Effects on torque angle curve of differences between the recorded tibia-calcaneal angle and the true anatomical angle. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol, 46(1), 41-46.

Tardieu, G., Tabary, J. C., Tardieu, C., & Tabary, C. (1973). [Proceedings: Influence of plaster-caste immobilization on the length of peroneus profundus muscle fibers in the cat. Comparative study on the soleus]. J Physiol (Paris), 67(3), 359A.

Tardieu, G., Tabary, J. C., Tardieu, C., Tabary, C., Gagnard, L., & Lombard, M. (1973). [Adjustment of the number of sarcomeres of the muscle fiber to its required length. Consequence of this regulation and of its disorders observed in neurology]. Rev Neurol (Paris), 129(1), 21-42.

Tardieu, G., & Tardieu, C. (1987). Cerebral palsy. Mechanical evaluation and conservative correction of limb joint contractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res(219), 63-69.

Tsao, H., Galea, M. P., & Hodges, P. W. (2008). Reorganization of the motor cortex is associated with postural control deficits in recurrent low back pain. Brain, 131, 6. doi:10.1093/brain/awn154

Tsao, H., Galea, M. P., & Hodges, P. W. (2010). Driving plasticity in the motor cortex in recurrent low back pain. Eur J Pain, 14(8), 832-839. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.01.001

Williams, P., Watt, P., Bicik, V., & Goldspink, G. (1986). Effect of stretch combined with electrical stimulation on the type of sarcomeres produced at the ends of muscle fibers. Exp Neurol, 93(3), 500-509.

Williams, P. E., & Goldspink, G. (1978). Changes in sarcomere length and physiological properties in immobilized muscle. J Anat, 127(Pt 3), 459-468.

Williams, P. E., & Goldspink, G. (1981). Connective tissue changes in surgically overloaded muscle. Cell Tissue Res, 221(2), 465-470.

Williams, P. E., & Goldspink, G. (1984). Connective tissue changes in immobilised muscle. J Anat, 138(2), 4.

Skills Demonstration

Case Study Author

Clinical Mentorship in the Integrated Systems Model

Join Diane, and her team of highly skilled assistants, on this mentorship journey and immerse yourself in a series of education opportunities that will improve your clinical efficacy for treating the whole person using the updated Integrated Systems Model.

We will come together for 3 sessions of 4 (4.5) days over a period of 6-8 months with lots of practical/clinical time to focus on acquiring the skills and clinical reasoning to put the ISM model into practice. Hours of online lecture and reading material and 12 hours of in-person lecture are...

More Info