Story

Tara is a physiotherapist and a mother of one child who is 13 months old. She presented with concerns about persistent, intermittent, pain in her low thorax and upper lumbar regions, as well as the visual profile of her 13-month post-partum abdomen. She was looking for ‘core strengthening’ guidance and thought that this would eliminate her back pain and improve the appearance of her abdomen. Tara also had questions regarding the pros and cons of a surgical repair of her abdominal wall, believing that she had a midline ‘hernia’ of her linea alba (LA). She had an uncomplicated pregnancy except for a series of incidents between 21 and 23 weeks when she felt a ‘ripping sensation’ of the LA just above the umbilicus. She felt this ‘ripping’ when she rolled in bed, ‘moved the wrong way’ or lifted heavy objects. Her baby was delivered by Caesarean-Section after her induced labour failed to progress following three hours of pushing.

Meaningful Complaint

Tara reported persistent, intermittent pain in her low thorax and upper lumbar regions, which would radiate to include her mid-thorax with increasing activity. Specifically, she felt achiness, fatigue and tenderness to touch localized to the area of the T8, T9 and T10 spinous processes. The onset of these symptoms was insidious, beginning a few months after her delivery, and localized to the thoracolumbar region initially. The symptoms progressed and spread to include the mid-thorax as she increased rotation loads through her trunk with running and kayaking. She did not report any associated, or independent, neurological symptoms such as pins/needles or numbness during any movements or loading of her trunk or extremities. On the Patient Specific Functional Scale (Horn et al 2012, Stratford et al 1995), she reported difficulty with lifting (6/10), running (2/10) and paddling her kayak (1/10). For this scale, 0 equals unable to perform the stated activity and 10 equals able to perform at pre-injury levels. Essentially, she found any task that required loading, especially repetitive rotation of the trunk, aggravating. Her pain was not exacerbated by static loading tasks, such as sitting or prolonged standing.

When asked more about her experience and limitations with running, Tara said it was easier for her to rotate her thorax to the left when she ran and felt she had to ‘pull her left shoulder forward’ to rotate to the right. When asked about her breathing, she reported difficulty breathing during her first two post-partum weeks: ‘I was unable to take a normal deep breath in standing. My upper abdomen would draw in and lower abdomen would pop out’. This symptom settled quickly but returned when she resumed running; she felt her breathing was ‘uncoordinated’. She did not report any urinary leakage with running or any other tasks that increased her intra-abdominal pressure.

Tara’s general health was good with no medical precautionary conditions present. Historically, she reported an episode of unilateral low back and pelvic girdle pain ten years prior that resolved when she reduced her ‘volume’ of dancing. She had not had her spine or thorax imaged.

Tara’s Personal Profile (Social History)

Tara was currently working four days per week in a private orthopaedic physiotherapy practice. Outside of work and caring for her family, she cross-country skied and attended both yoga and Pilates classes. She had not been able to return to running or kayaking at her pre-pregnancy levels, two activities she missed.

Cognitive Belief

Tara believed that she had an abdominal hernia due to tearing of her LA and that this was the result of the series of ‘ripping sensations’ she experienced in the second trimester of her pregnancy. In addition, she felt that her abdominal muscles were weak and that in compensation she was over-using her back muscles, but she did not feel she knew how to correct this imbalance. She believed that her over-used back muscles were contributing to the thoracolumbar ache and fatigue, as well as the local tenderness she experienced when the T8, T9 or T10 spinous processes were palpated. Tara also questioned whether it was possible to restore optimal strength of her abdominal wall without surgical repair of the hernia. She was coping well with both her work and home duties and did not appear overly vigilant to her pain or anxious/worried when telling her story. She was frustrated by her lack of ability to return to her pre-pregnancy levels of fitness and sport, which would seem a reasonable emotion given her circumstances.

Reasoning Question

Tara’s story of back pain present for approximately 15 months would be broadly classified as non-specific chronic musculoskeletal pain by many clinicians. Such presentations are frequently linked to maladaptive central nervous system (CNS) sensitization. On the basis of Tara’s story, would you discuss your hypotheses regarding the dominant ‘Pain Type’ (nociceptive, neuropathic, maladaptive CNS sensitization) in her presentation and whether you feel there were any psychosocial factors that may have contributed to the maintenance of her pain and disability?

Answer to Reasoning Question

While I would agree that Tara’s back pain could be classified as non-specific and chronic, I didn’t believe it was only due to sensitization of her CNS. When her physical, social and emotional behaviours are considered, there were no indications that she was catastrophizing, hypervigilant or demonstrating other maladaptive behaviours/beliefs associated with dominant central sensitization. She continued to work four days per week, ski and participate in yoga and Pilates classes. Her symptoms were localized and consistent with a nociceptive pattern of aggravation; thus, it was more likely that her pain was peripherally mediated even though it was chronic. Her beliefs were realistic given the history of events during her pregnancy and worth exploring through physical examination of the abdominal wall. If she did tear the LA and does have herniation of the abdominal contents, her ability to stabilize the joints of her low back and pelvis would be compromised due to loss of the force closure mechanism (Vleeming et al 1990a,b).

Reasoning Question

Given your hypothesis of a nociceptive dominant presentation, what structures/tissues do you hypothesise as possible nociceptive sources to her pain?

Answer to Reasoning Question

At this point in the examination, I felt the structures that were potential nociceptive sources to her pain were likely multiple, and possibly enthesopathic. Nociception could be generated from one, or any combination, of attachments of several muscles directly, or indirectly through the thoracolumbar fascia, to the spinous processes of T8-10. I did not hypothesize that the costovertebral or zygapophyseal joints of the thoracolumbar region were contributing much to her pain since ‘achiness’ and ‘general fatigue’ are not usual symptoms of an articular source of nociception.

Reasoning Question

Tara indicated that she believed her lack of abdominal strength was causing her to overuse her back muscles which then caused her symptoms. Would you please discuss your interpretation of Tara’s beliefs and any associated implications for your physical examination?

Answer to Reasoning Question

I felt that Tara’s perspective of her problem was accurate in that she was likely over-using her back muscles and under-using her abdomen; however, I felt that the underlying cause of her ‘abdominal weakness’ and lack of improvement was less likely due to her ‘core strength’ and more likely due to either changes in the structure of her abdominal wall and/or her motor control strategies induced by her pregnancy.

Pregnancy and delivery present huge challenges for the abdominal wall and back. Lumbopelvic pain (Albert et al 2001, 2002, Larsen et al 1999, Östgaard et al 1991, 1996), motor control changes of the abdominal wall (Beales et al 2008, O’Sullivan et al 2002, Smith et al 2007, Stuge et al 2006) and diastasis rectus abdominis (DRA) (Boissonault & Blaschak 1988, Gilleard & Brown 1996, Liaw et al 2011, Mota et al 2014) are common both during and after pregnancy. With respect to the structure of the abdominal wall, while evidence is limited, it appears that for some recovery is not spontaneous without intervention (Coldron et al 2008, Liaw et al 2011, Mota et al 2014).

From Tara’s story, two aspects of abdominal wall function would need to be assessed:

- The structural integrity of the LA and the ability of the abdominal wall to transfer load.

- Her ability to synergistically recruit the deep (transversus abdominis (TrA)) and superficial (internal (IO) and external oblique(s) (EO) and rectus abdominis (RA)) abdominal muscles with the other muscles of her core (back and pelvic floor muscles).

Clinical Reasoning Commentary

Consideration of pain type (e.g. nociceptive versus maladaptive CNS sensitization dominant) is a principal ‘Hypothesis Category’ discussed in Chapter 1 with significant implications for other clinical decision categories such as potential sources of nociception, precautions to examination and treatment, management and prognosis. While chronicity is often associated with maladaptive sensitization, as highlighted in the Answer to Question 1, this is not always the case. Maladaptive catastrophizing, hypervigilance and fears, along with social and behavioural factors, are considered here but found not to be evident and the behaviour of symptoms is instead judged to be more consistent with a nociceptive dominant presentation. This highlights the reality that pain and disability also can be maintained, in part or full, by continued physical stress and aggravation related to misconceptions (e.g. beliefs about the problem and what is needed, such as insufficient ‘core’ strength), behaviour (e.g. continued stress and aggravation from activities such as running and kayaking), environmental and social factors (not evident here) and physical factors screened later in the physical examination (e.g. alignment, mobility and control).

As discussed in Chapter 1, clinical patterns are not limited to diagnostic classifications of pathologies or syndromes as they also exist with regard to physical, environmental and psychosocial contributing factors, pain type, precautions/contraindications and prognosis. The Answer to Question 3 reflects recognition of an evidence-informed clinical pattern of impaired motor control strategies induced by pregnancy with plans to test the hypothesis through specific physical examination assessments.

Meaningful Tasks

Three tasks, based on Tara’s goals, were chosen for evaluation. These tasks also relate to the known function of the abdominal wall:

- Standing posture (position from which lifting and running begins)

- Supine lying curl-up task (requires co-ordinated activation of all abdominal muscles)

- Seated trunk rotation with and without resistance (essential for running and kayaking)

Flexion, extension and sideflexion of the trunk were not tested since these cardinal plane motions, in isolation, do not specifically relate to the aggravating component (trunk rotation) of her meaningful tasks (running and paddling). In addition, no specific neurodynamic tests were included in this examination since there was no indication from her story that this system was contributing to her complaints or her functional limitations.

Standing Posture – Relevant Positional Findings of the Trunk

Tara was not experiencing any pain or discomfort in her thorax or upper lumbar spine at the time of this examination. In standing, her pelvis was rotated to the right in the transverse plane. Her lower thorax was rotated to the left and her middle thorax was rotated to the right. Segmental thoracic ring shifts (Lee L-J 2003a) were noted in both regions of the thorax. Specifically, the 8th thoracic ring was shifted to the right and the 9th to the left. The 4th thoracic ring was shifted to the left and the 3rd to the right.

Reasoning Question

Would you please explain the key features you assess during your analysis of standing posture and how you determine whether asymmetries identified are relevant or not to that patient’s presentation?

Answer to Reasoning Question

This is a great question and highly appropriate since many clinicians get ‘bogged down’ with findings that at the end of the examination have no clinical relevance. Meanwhile, they are overwhelmed by information and what it all means.

Standing is the starting point for many functional tasks including:

- Standing for prolonged periods of time

- Sitting

- Squatting

- Lifting

- Running

- Climbing stairs

- Reaching overhead

A quick screen of standing posture allows the clinician to interpret what happens during movement more accurately. Very few of us stand perfectly aligned and asymmetries in multiple regions of the body are common. So, when are they relevant to the clinical picture? In short, they are relevant when the individual is held in the asymmetric position and is unable to move, or control, the asymmetric region when they need to do so. For example, in standing it is common to find the pelvis rotated in one direction in the transverse plane and the thorax rotated in the opposite direction. For a squat task, both of these transverse plane rotations should unwind and the pelvis and thorax should align symmetrically. Loads are increased through the lumbar spine if the thorax and pelvis remain rotated in opposite directions during the squat (Al-Eisa et al 2006).

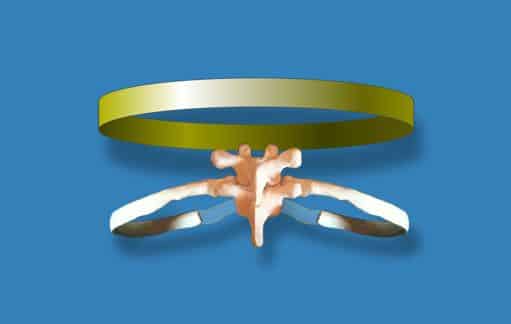

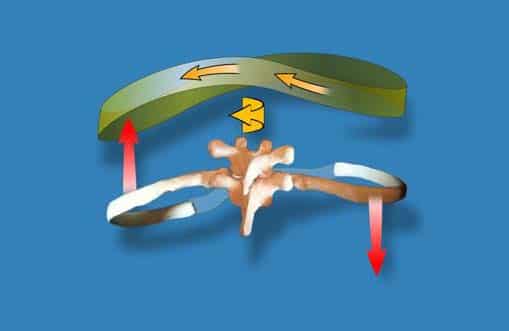

Figure 1a – A thoracic ring is defined as two adjacent thoracic vertebrae, the left and right ribs of the same number as the inferior vertebra, the sternum or manubrium to which the ribs attach and all the joints that connect these bones (Lee D 1994).Figure 1b – The biomechanics of right rotation of a typical thoracic ring (Lee D 1993, 2015). Left lateral translation occurs in conjunction with right rotation of the thoracic ring. The right rib posteriorly rotates, the left rib anteriorly rotates and at the end of the available range the thoracic spinal segment rotates and sideflexes to the right.A thoracic ring is defined as two adjacent thoracic vertebrae, the left and right ribs of the same number as the inferior vertebra, the sternum or manubrium to which the ribs attach and all the joints that connect these bones (Lee D 1994) (Figure 1a). Each thoracic ring has the potential to rotate in the same or opposite direction to the one above/below. So while a quick screen of the thorax is regional (lower, middle, upper), a more detailed segmental thoracic ring analysis considers the positional relationship between each thoracic ring and provides information as to which thoracic ring is ‘driving’ the regional rotation. Linda-Joy Lee has developed novel assessment techniques (Lee L-J 2003a, b, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2012) for analysis of both position and mobility of an entire thoracic ring. These particular tests, combined with biomechanical and arthrokinematic mobility tests (Lee D 1993, 1994, 2003), were used to understand the clinical relevance of Tara’s specific thoracic rings shifts as noted above.

A thoracic ring shift is another way of saying that the thoracic ring is positioned in rotation. The word ‘shift’ refers to the direction of translation of a thoracic ring, which is a congruent motion that occurs when the thoracic ring rotates (Lee D 1993) (Figure 1b). This translation is easy to detect when the thoracic ring position is assessed in the mid-axillary line (Lee L-J 2003a, 2005, 2008, 2012).The clinical relevance of each asymmetry is determined by correcting the rotation/shift and assessing:

- Whether a correction is possible or not (stiff, fibrotic or fixated joints will not allow the alignment of the thoracic or pelvic ring to correct)

- The impact of the correction on the position/alignment of the other noted asymmetries

- The impact of the correction on performance of the task being evaluated (standing posture, squat, arm elevation, one leg stand etc.)

- The impact of the correction on the patient’s symptom experience (pain, tingling, burning, ability to breathe etc.)

Essentially, to understand the relationship between the thoracic rings and the pelvis, look for the ‘ring’ whereby the biggest resultant change in posture/position is created by a single or combined correction. Then determine if this correction also improves the alignment, biomechanics and/or control of other regions of the body during the task being evaluated.

In The Integrated Systems Model for Disability and Pain (Lee L-J & Lee D 2011), this is called ‘Finding the Primary Driver’. Of note, the position of the trunk (thorax and pelvis) can also be influenced by the posture/position of the lower extremity, shoulder girdle, head and neck, so the ‘driver’ may not be within the trunk!

Clinical Reasoning Commentary

Postural asymmetries fall under the hypothesis category of ‘Contributing Factors’. Like all health risk factors, they will not always result in symptoms or dysfunction as they represent only one factor within the biopsychosocial makeup that determines health and function. Therefore, as emphasised in this Answer, clinicians must have a clear rationale for each assessment performed, and since asymptomatic postural asymmetries are common, specific strategies for judging their likely relevance to an individual’s presentation are essential.

Tara had five segments within her trunk that were not optimally aligned in standing: the 3rd, 4th, 8th and 9th thoracic rings, as well as the pelvis. To determine the clinical relevance of these asymmetries, a series of regional and segmental asymmetry corrections were made. When her pelvis was manually corrected (to derotate the right transverse plane rotation and center her pelvis over her feet), the alignment of both her lower and middle thorax was worse. Overall, her standing posture was worse and she felt more twisted with this correction. This suggested that treating her pelvic alignment directly would not improve the overall posture of her trunk in standing. In addition, her ability to paddle her kayak and run would not improve if her thorax was more ‘twisted’.

When the 8th thoracic ring was manually corrected (derotate/correct the segmental thoracic rotation/shift to align the adjacent rings), the position of the 9th thoracic ring improved spontaneously, as did the alignment of her pelvis. This suggested that treatment directed towards correcting the alignment of her 8th thoracic ring would improve both the 9th thoracic ring and the pelvic posture in standing. However, this correction did not change the position of the 3rd or 4th thoracic rings. Correcting the 4th thoracic ring improved the 3rd, but not the 8th or 9th rings.

Tara’s standing posture improved the most when both the 4th and 8th thoracic rings were manually corrected simultaneously. None of these manual corrections provoked any symptoms in her thorax or upper lumbar spine. Conversely, Tara noticed the automatic correction in the alignment of her pelvis when her 4th and 8th thoracic rings were simultaneously aligned. She felt ‘less twisted’ and actually had not realized that she was twisted until the two thoracic ring corrections (4th and 8th) were released.

Correcting the alignment of two of her thoracic rings made Tara aware of the relationship between her thorax and pelvis in standing. Her existing body schema was twisted (Berlucchi 2010) but she was unaware of this until the twist was reversed and she ‘attended’ to the response of her body as the correction was released. This is often a ‘Wow’ moment for patients when they realize where they are ‘living in their bodies’ (i.e. acquire a new body schema). Focused attention and awareness are two key conditions necessary for change; these are neuroplastic principles increasingly recognized as critical for musculoskeletal rehabilitation (Boudreau et al 2010, Snodgrass et al 2014, van Vliet et al 2006).

When standing, the profile of Tara’s relaxed abdomen was protuberant and when asked to ‘connect to her core’ excessive activation of the EO abdominals occurred. While this strategy drew her abdomen inward, it did not eliminate the protrusion completely (Figure 2a,b). Her abdomen continued to appear, and feel, highly pressurised.

When the 4th and 8th thoracic rings were manually corrected immediately prior to Tara’s ‘connect’ cue, she noticed a decrease in the pressure sensation of her lower abdomen and when attention was directed to the profile of her abdomen she was pleasantly surprised at the change.

Reasoning Question

Please discuss how you relate your analysis of regional and segmental postural corrections to contemporary motor control theory and highlight what you attend to visually, kinaesthetically and via patient response in determining their relevance. Would you also comment on the current levels of evidence underpinning this assessment?

Answer to Reasoning Question

Multiple studies suggest that the response to back pain is individual and task specific (see review article on pain and motor control: Hodges 2011), although there are common features to most clinical presentations. Hodges (2011 p 222) notes that back pain patients present with a “redistribution of activity within and between muscles (rather than inhibition or excitation of muscles in a stereotypical manner)”. All of the multisegmental muscles of the trunk contribute to movement and control and when their activity is ‘redistributed’, they can produce specific vectors of force that contribute to thoracic ring shifts and pelvic rotations. Thus, Hodges states ‘If the goal of rehabilitation (e.g. using motor learning strategies) is to modify the adaptation (remove, modify or enhance) then this needs to be considered on an individual basis with respect to the unique solution adopted by the patient’ (Hodges 2011 p 222-223).

The clinician’s challenge is to determine which muscles are ‘actors’ (creating the primary vector of force) and which are ‘reactors’ (reacting to the primary vector). Increased muscle activation noted on palpation or during a certain posture (standing, sitting) or task (seated trunk rotation, single leg standing) does not mean that this muscle should be released or stretched. Releasing ‘reactors’ allows the primary muscle (the actor) to increase the rotation/twist (and often the symptoms). Therefore, when looking for the driver, the clinician should also pay attention to the vectors of resistance to movement encountered during specific corrections and the location, direction, length and velocity of pull of the vector upon release of the correction. This vector analysis provides further information about the underlying source of the pull (articular, myofascial, neural, visceral) (Lee D, Lee L-J 2011a).

The patient is engaged (focused attention and awareness) in this entire ‘correct and release’ process and is asked to provide feedback on their experience. Symptoms should not increase when the driver is corrected; rather, a sense of well being, or ease, in the body is desirable, as is an improvement in the ability to breathe or any lessening of intra-abdominal, intra-thoracic or intra-cranial pressure. Less effort should be required to perform the task when the driver is held in a corrected position and the alignment, biomechanics and control are facilitated.

I am unaware of any research that has considered changes in the ‘gestalt’ of the patient’s experience specifically with thoracic ring corrections, or any research that has investigated the impact of thoracic ring corrections on pelvic position, hip position, foot position etc. Currently, there are no measuring systems that are able to accurately measure segmental thoracic ring position or mobility, nor intra-pelvic mobility. These are clinical observations.

Clinical Reasoning Commentary

Application of research evidence to practice is challenging and requires judgment regarding the applicability of findings from the population studied to your patient and their context, and whether the intervention can be replicated in the clinic. Often insufficient information is reported on precisely what was implemented in the study, including details of treatment (e.g. positions, dosage, sequence, progression), patient-therapist therapeutic alliance (e.g. rapport, collaboration) or therapeutic education (e.g. explanations, advice, instructions) to enable clinicians to replicate the assessments and management (educatively, behaviourally and humanistically) with confidence. In the absence of empirical research evidence, as acknowledged here, existing biologically plausible theory (e.g. Hodges 2011) can be applied to clinical practice, combined with careful monitoring of individual treatment effects to guide reasoning and overall management. While monitoring of outcomes to judge overall success will include any changes in the patient’s activity (function) and participation restrictions and capabilities, monitoring (reassessment) to determine relevance of physical findings, specific treatment interventions and progression of treatment requires attention to broader and more detailed (often qualitative) variables as discussed here. These can include patient awareness and individual muscle activation patterns, and their effects on patient symptoms, thoughts, movement control, and other body sensations experienced during the functional task.

Supine Curl-up Task

The supine curl-up task was chosen to evaluate Tara’s abdominal wall and LA, since this task should involve co-activation of all muscles of the abdominal wall (Andersson et al 1997). With no cue, or instruction, Tara’s automatic strategy for the supine curl-up task produced more bulging of her abdomen and asymmetric narrowing of the infrasternal angle (right side greater than left) (Figure 3a,b).

When she held the curl-up position, the left and right recti could be easily separated along the entire length of the LA (Figure 4) by hand. The inter-recti distance (IRD) was two finger widths (during the curl-up) and of particular note was the lack of tension in the LA. This task did not provoke any symptoms in her thorax or upper lumbar spine.

Ultrasound imaging (UI) provided more information on Tara’s abdominal wall function:

- UI of the lateral abdominal wall during a supine curl-up using an automatic strategy: Tara had difficulty co-activating the right TrA and IO compared to the left.

- UI of the LA during a supine curl-up using an automatic strategy: just above the umbilicus the IRD was 2.55cm at rest and narrowed to 1.99cm during the curl-up. The LA appeared distorted or slack, a finding consistent with the previously noted lack of palpable tension.

- UI of the lateral abdominal wall during a supine curl-up using a ‘connect to core cue’ strategy: Tara was able to produce an isolated contraction of both the left and right TrA when she used imagery and cues to activate her pelvic floor (Sapsford et al 2001); however, she was not able to sustain activation of the right TrA and perform a curl-up task unless she manually corrected the 8th thoracic ring (Lee L-J 2007) (also noted to be shifted to the right in supine lying).

- UI of the LA during a supine curl-up while correcting the alignment of the 8th thoracic ring in addition to using a ‘connect to core cue’ strategy: just above the umbilicus the IRD widened to 2.85cm and the distortion of the LA decreased (Figure 5). Both of these imaging findings suggested that tension of the LA increased with this combined strategy, and this was confirmed with manual palpation.

Reasoning Question

DRA assessment (manually and via ultrasound) will be less familiar to many clinicians. Please discuss this in the context of your broader motor control assessment and highlight your hypotheses regarding Tara’s findings with respect to her complaints and your management.

Reasoning Answer

There is very little evidence to guide management of post-partum women with DRA (Beer et al 2009). Which patients are appropriate for conservative treatment and which ones will also require surgery? The distance between the left and right rectus abdominis (IRD) has been investigated in women through pregnancy and beyond, and it is thought that 100% of women have widening of the LA (increase in the IRD) during pregnancy (Gilleard & Brown 1996, Mota et al 2014) but that some remain abnormally widened in the post-partum period (Coldron et al 2008, Liaw et al 2011, Mota et al 2014). UI is a reliable method for evaluating the IRD (Coldron et al 2008, Mendes et al 2007, Mota et al 2012).

Many believe that the DRA should ‘close’ for restoration of optimal function of the abdominal wall (Mota et al 2012, Tupler et al 2011). While this may seem intuitive, our clinical experience with over 100 women with DRA revealed that the DRA ‘opened’ (IRD became wider) as their abdominal wall function improved. This finding led us to question the goal of restoring strategies that merely ‘close’ the DRA. This was later confirmed by our research (Lee & Hodges (submitted)) that suggested that the ability to generate tension of the LA is more important than the IRD and that training strategies that merely reduce the IRD may be sub-optimal for function.

Pascoal et al (2014 p 4) noted that in post-partum women the IRD decreased during a curl-up task and suggested that:

‘abdominal strengthening exercises contribute to the narrowing of the inter-rectus distance in postpartum women. However, research should be undertaken to evaluate which exercises are the most effective and safe for reduction of the inter-rectus distance in postpartum women.’

This suggests that exercises should be chosen that reduce the IRD, in other words, close the gap. Mota et al (2012) found that the IRD was greater during an abdominal ‘drawing-in exercise’ than in both the rest position and an ‘abdominal crunch’ in their study of post-partum women. Our results for the IRD during a curl-up task in post-partum women with DRA (Lee & Hodges (submitted)) concur with the findings of both Mota et al and Pascoal et al; however, our conclusions from the results and recommendations for treatment differ since we also considered the distortion/laxity response of the LA during two different strategies for this task.We investigated the LA in two conditions; an automatic curl-up strategy and a strategy with a cue to pre-contract the TrA prior to the curl-up. In our healthy, nulliparous controls, the IRD remained unchanged during the curl-up task with or without pre-activation of TrA. In other words, the LA in our healthy controls did not distort; it remained tensed. In the subjects with DRA, the IRD narrowed from the rest position during an automatic curl-up strategy and widened compared to their automatic strategy when they pre-activated TrA. These findings suggest that co-activation of the abdominals will widen the IRD and is more likely to generate tension across the LA (i.e. create less distortion).

Clinically, it appears that generating tension in the LA (create less distortion) is more important than closing the IRD. Those who can achieve co-activation strategies of the abdominal wall that are synergized with appropriate activation of the diaphragm, pelvic floor muscles and back muscles are able to transfer loads with better alignment, biomechanics and control. Clinicians often note the depth of the LA during a curl-up task and question the significance of this finding. We feel that this is merely a reflection of the distortion (laxity) of the LA during this task, the greater the distortion the deeper you can push the LA into the abdomen (Lee & Hodges (submitted)).

Tara did not have a tear of her LA (contrary to her her cognitive belief). Structural integrity of the LA could be imaged throughout its entire length and there was no herniation of abdominal contents. She did have a sub-optimal motor control strategy of the abdominal muscles during the automatic curl-up task in that she had difficulty recruiting the right TrA. This asymmetric abdominal activation appeared to contribute to the distortion of the LA, resulting in insufficient tension for transferring loads. When the 8th thoracic ring shift was corrected, she was able to recruit the right TrA and co-activate it with the rest of the abdominals during the curl-up. Co-activation of all her abdominals widened the IRD resulting in less distortion of the LA.

Tara’s IRD at rest (25.5 mm) classifies her as having a DRA according to Beer et al (2009) (IRD greater than 13mm ± 7mm just above the umbilicus). The clinical and UI findings suggested her DRA was functional and not requiring surgery; findings from the next test would confirm or negate this hypothesis.

Clinical Reasoning Commentary

This analysis represents an example of ‘Inference to the best explanation’ (or abduction) as discussed in Chapter 1. In the absence of research validated criteria for deducing the effects of abdominal activation strategies (e.g. automatic curl-up versus curl-up with pre-activation of TrA) on the LA and controlled load transfer in women with DRA, extensive clinical experience led to the discovery of patterns in previously unlinked information (LA tension as opposed to IRD) through ‘Inference to the best explanation’. This culminated in the clinical recognition/theory that LA tension generated through abdominal wall co-activation is more important than IRD to load transfer and function. The ‘clinical evidence’ regarding load transfer and function was confirmed with research that investigated the effects of different activation strategies on the LA. While research is essential to test clinical theory, clinical practice cannot be limited to research-validated knowledge (assessment and management) because it only forms one of the three elements of evidence-informed practice, the others being clinical expertise and patient values (see Chapter 5). Critical, reflective clinical reasoning, incorporating deductive and inductive inferences on the basis of what is ‘known’, and on consideration of the ‘best explanation’ when dealing with areas that are less well understood, safeguards against errors in reasoning (see Chapter x) and enables the discovery of new knowledge. The clinical relevance and therapeutic efficacy for the individual patient, as discussed here, will always be essential to establish.

Seated Trunk Rotation With and Without Resistance

Increased effort was required for Tara to rotate her thorax to the right and when the 8th thoracic ring shift (to the right) was manually corrected, her range of right rotation increased and her effort to perform this task decreased (Lee L-J 2003a, 2012). No symptoms other than ‘resistance’ and ‘effort’ were reported during the seated trunk rotation task. A similar finding was noted with respect to the 4th thoracic ring that was shifted to the left and restricting left thoracic rotation. Left rotation of the trunk/thorax improved with manual correction of the 4th thoracic ring (range of motion improved and the effort to perform the task was reduced). A simultaneous correction of both the 4th and 8th thoracic rings did not further improve either right or left thoracic rotation; a single ring correction was enough for each direction.

When a resisted left rotation load was applied to the trunk through her bilaterally elevated arms, marked loss of low thorax control was evident (Figure 6a). In spite of the loss of regional alignment and control, no pain was provoked with this single (non-repetitive) loading task. When instructed (cued) to pre-activate TrA prior to loading, Tara’s trunk control improved when resistance was applied to right trunk rotation but not to left rotation. Previous evaluation via UI revealed that the 8th thoracic ring required correction before activation of the the right TrA was sustained. When the alignment of the 8th thoracic ring was corrected and its position controlled during the application of the left rotation load, Tara’s low thorax/upper lumbar control, as well as her ‘experience of core rotation strength’ significantly improved (Figure 6b). The ‘gestalt’ of Tara’s experience in her body was related to function and performance, as opposed to the provocation/alleviation of pain during this assessment.

Reasoning Question

DRA assessment (manually and via ultrasound) will be less familiar to many clinicians. Please discuss this in the context of your broader motor control assessment and highlight your hypotheses regarding Tara’s findings with respect to her complaints and your management.

Reasoning Answer

There is very little evidence to guide management of post-partum women with DRA (Beer et al 2009). Which patients are appropriate for conservative treatment and which ones will also require surgery? The distance between the left and right rectus abdominis (IRD) has been investigated in women through pregnancy and beyond, and it is thought that 100% of women have widening of the LA (increase in the IRD) during pregnancy (Gilleard & Brown 1996, Mota et al 2014) but that some remain abnormally widened in the post-partum period (Coldron et al 2008, Liaw et al 2011, Mota et al 2014). UI is a reliable method for evaluating the IRD (Coldron et al 2008, Mendes et al 2007, Mota et al 2012).

Many believe that the DRA should ‘close’ for restoration of optimal function of the abdominal wall (Mota et al 2012, Tupler et al 2011). While this may seem intuitive, our clinical experience with over 100 women with DRA revealed that the DRA ‘opened’ (IRD became wider) as their abdominal wall function improved. This finding led us to question the goal of restoring strategies that merely ‘close’ the DRA. This was later confirmed by our research (Lee & Hodges (submitted)) that suggested that the ability to generate tension of the LA is more important than the IRD and that training strategies that merely reduce the IRD may be sub-optimal for function.

Pascoal et al (2014 p 4) noted that in post-partum women the IRD decreased during a curl-up task and suggested that:

‘abdominal strengthening exercises contribute to the narrowing of the inter-rectus distance in postpartum women. However, research should be undertaken to evaluate which exercises are the most effective and safe for reduction of the inter-rectus distance in postpartum women.’

This suggests that exercises should be chosen that reduce the IRD, in other words, close the gap. Mota et al (2012) found that the IRD was greater during an abdominal ‘drawing-in exercise’ than in both the rest position and an ‘abdominal crunch’ in their study of post-partum women. Our results for the IRD during a curl-up task in post-partum women with DRA (Lee & Hodges (submitted)) concur with the findings of both Mota et al and Pascoal et al; however, our conclusions from the results and recommendations for treatment differ since we also considered the distortion/laxity response of the LA during two different strategies for this task.We investigated the LA in two conditions; an automatic curl-up strategy and a strategy with a cue to pre-contract the TrA prior to the curl-up. In our healthy, nulliparous controls, the IRD remained unchanged during the curl-up task with or without pre-activation of TrA. In other words, the LA in our healthy controls did not distort; it remained tensed. In the subjects with DRA, the IRD narrowed from the rest position during an automatic curl-up strategy and widened compared to their automatic strategy when they pre-activated TrA. These findings suggest that co-activation of the abdominals will widen the IRD and is more likely to generate tension across the LA (i.e. create less distortion).

Clinically, it appears that generating tension in the LA (create less distortion) is more important than closing the IRD. Those who can achieve co-activation strategies of the abdominal wall that are synergized with appropriate activation of the diaphragm, pelvic floor muscles and back muscles are able to transfer loads with better alignment, biomechanics and control. Clinicians often note the depth of the LA during a curl-up task and question the significance of this finding. We feel that this is merely a reflection of the distortion (laxity) of the LA during this task, the greater the distortion the deeper you can push the LA into the abdomen (Lee & Hodges (submitted)).

Tara did not have a tear of her LA (contrary to her her cognitive belief). Structural integrity of the LA could be imaged throughout its entire length and there was no herniation of abdominal contents. She did have a sub-optimal motor control strategy of the abdominal muscles during the automatic curl-up task in that she had difficulty recruiting the right TrA. This asymmetric abdominal activation appeared to contribute to the distortion of the LA, resulting in insufficient tension for transferring loads. When the 8th thoracic ring shift was corrected, she was able to recruit the right TrA and co-activate it with the rest of the abdominals during the curl-up. Co-activation of all her abdominals widened the IRD resulting in less distortion of the LA.

Tara’s IRD at rest (25.5 mm) classifies her as having a DRA according to Beer et al (2009) (IRD greater than 13mm ± 7mm just above the umbilicus). The clinical and UI findings suggested her DRA was functional and not requiring surgery; findings from the next test would confirm or negate this hypothesis.

Clinical Reasoning Commentary

This analysis represents an example of ‘Inference to the best explanation’ (or abduction) as discussed in Chapter 1. In the absence of research validated criteria for deducing the effects of abdominal activation strategies (e.g. automatic curl-up versus curl-up with pre-activation of TrA) on the LA and controlled load transfer in women with DRA, extensive clinical experience led to the discovery of patterns in previously unlinked information (LA tension as opposed to IRD) through ‘Inference to the best explanation’. This culminated in the clinical recognition/theory that LA tension generated through abdominal wall co-activation is more important than IRD to load transfer and function. The ‘clinical evidence’ regarding load transfer and function was confirmed with research that investigated the effects of different activation strategies on the LA. While research is essential to test clinical theory, clinical practice cannot be limited to research-validated knowledge (assessment and management) because it only forms one of the three elements of evidence-informed practice, the others being clinical expertise and patient values (see Chapter 5). Critical, reflective clinical reasoning, incorporating deductive and inductive inferences on the basis of what is ‘known’, and on consideration of the ‘best explanation’ when dealing with areas that are less well understood, safeguards against errors in reasoning (see Chapter x) and enables the discovery of new knowledge. The clinical relevance and therapeutic efficacy for the individual patient, as discussed here, will always be essential to establish.

Vector Analysis - 8th Thoracic Ring Assessment

Further testing was done to determine why the 8th thoracic ring was translated to the right/rotated to the left in standing, sitting and lying and failed to transfer loads effectively during resisted left trunk rotation. Findings from these tests resulted in the following observations/deductions:

- The joints of the 4th and 8th thoracic rings demonstrated normal mobility and passive integrity and testing did not provoke pain (Lee D 2003). This is consistent with the finding that both the 4th and 8th thoracic ring shifts were manually correctable.

- Increased resting tone was noted in the right EO, specifically in the part of this muscle that attaches to the anterior aspect of the right 8th rib (Figure 3). The attachment of the right EO to the 8th rib was tender on local palpation. The increased EO tone, and the resultant vector of force it produced on the right 8th rib, was palpable when manually correcting the alignment of the 8th thoracic ring; however, the local tenderness/discomfort was not reproduced with this manual correction, only with direct palpation. The 9th thoracic ring shift to the left corrected when the 8th ring was aligned, suggesting that its position was compensatory.

- No apparent atrophy, or inhibition, of the deep segmental muscles pertaining to the 8th thoracic ring was palpable (i.e. multifidus/rotatores or intercostals).

Reasoning Question

Please discuss your interpretation of the additional tests of the joints of the 4th and 8th thoracic rings and Tara’s seated trunk rotation findings with respect to their support, or not, to your previous hypotheses regarding potential sources of nociception and physical contributing factors.

Answer to Reasoning Question

I felt that Tara had developed sub-optimal recruitment strategies for both mobility and control of the 4th, 8th (primary) and 9th (compensatory) thoracic rings during at least three functional tasks: standing, supine curl-up and seated trunk rotation. These sub-optimal strategies were impacting her ability to transfer loads through her trunk when lifting, running and kayaking. In particular, her right thoracic rotation was limited by the 8th thoracic ring shift to the right, which may have resulted in her ‘need’ to pull the left shoulder forward when right rotating her thorax during running. This strategy would require more effort and could have been a contributing factor to both the fatigue and mid-thoracic pain she felt with the repetitive rotational requirement of running. The 4th and 8th thoracic ring restrictions in opposite directions of rotation would impact her mobility and strategies for kayaking, again possible factors for her muscular fatigue and aching with repetitive rotation loads.

The passive assessments of the joints of the 4th and 8th thoracic rings revealed normal mobility (consistent with the finding that the thoracic ring position and mobility could be influenced by gentle manual correction) and did not provoke her pain. In a hypothesised nociceptive dominant presentation such as Tara’s, this supports that the joints are not a pathological source of nociception, rather they, along with the local muscles, may be over-stressed and perhaps nociceptive sources secondary to her alignment and control impairments. Clinically this will require interventions targeted to her control and alignment to determine their influence.

Her sensation and belief that her ‘core’ was weak was likely due to dys-synergies between the abdominal muscles in that there was over-activation of the right EO and under-activation of the right TrA. This is likely a clinical example of ‘redistribution of activity within and between muscles’ as noted by Hodges (2011.) This strategy was having an impact on her ability to generate tension in the LA throughout its length and thus control the joints of the low thorax and lumbar spine during rotation loading. This hypothesis was further supported by the findings of the resisted trunk rotation test in sitting.The focus of this assessment was to determine why her low thorax/upper lumbar spine failed to maintain optimal alignment, biomechanics and control, as opposed to identifying the pain generators. It was hypothesized that repetitive loss of segmental control would compress/stress/irritate multiple structures (costotransverse and zygapophyseal joints, intervertebral discs, myofascial tendinous insertions etc.), pain from which is often difficult to reliably isolate.

Tara had physical impairments that were relevant and proportional to her activity and participation restrictions, combined with no overt physical signs of CNS sensitization (e.g. allodynia, widespread tenderness) which taken together further support the previous hypothesis of a nociceptive dominant pain type/mechanism.

Clinical Reasoning Commentary

Hypotheses formulated during the subjective examination should be ‘tested’ against findings from the physical examination, and again later through reassessments to specific interventions. Here the physical findings were judged to be consistent with the previously hypothesised nociceptive dominant pain type/mechanism. The potential for stress, and hence nociception, of multiple structures is acknowledged. However with red flags and overt symptomatic pathology already ruled out, and both functional and spinal assessments being non-provocative, precise structural differentiation for Tara’s thoracic pain was not likely possible or required. Instead, clinical ‘diagnostic differentiation’ of her non-specific spinal pain gives way to a focus on physical impairments that may have been contributing to her functional restrictions. Tara’s pain and functional restrictions were hypothesised to be due to ‘dys-synergies between the abdominal muscles’. However, it is important to recognise that judgment is not reached on the basis of neuromuscular assessment alone; rather it is predicated on both positive and negative findings from a range of advanced clinical and manual assessments, including observation of posture, analysis of functional tasks related to her activity restrictions, thoracic ring mobility and pain provocation, observation and palpation of muscle bulk and tone, and effects of thoracic ring corrections on position/alignment of other asymmetries and functional tasks being evaluated. A likely clinical pattern of muscle dys-synergy may have been recognised back in the subjective examination, but physical assessments of mobility and pain provocation were still performed and ultimately it is the combined picture of negative and positive findings that ‘confirm’ the suspected pattern.

Treatment

Treatment – First Session

The EO vector (i.e. tension) that was preventing the 8th thoracic ring from moving optimally during right rotation of the thorax was released (reassessed by palpation) using a positional release technique (Lee D, Lee L-J 2011b). Subsequently, the 8th thoracic ring was no longer held in left rotation/right translation (repeated standing posture assessment) and the amplitude of her active right thoracic rotation increased. Tara noticed an immediate decrease in the effort required to rotate her thorax to the right (repeated seated trunk rotation without resistance). The resting tone of the part of the EO attaching to the right 8th rib was significantly reduced on palpation. When a left rotation load was applied to the trunk through her bilaterally elevated arms, she was still unable to control her lower thorax suggesting that her motor control strategy was still not optimal for regional control of the low thorax.

Tara was then taught a home exercise to maintain the reduced tone and optimal length specifically in this part of the EO. This required manual correction and stabilization of the right 8th rib (part of the 8th thoracic ring) as she then rotated her pelvis (and legs) to the left in supine lying. This exercise is a modified ‘Wipers Pose’ in yoga. At the initiation of the task, inhalation is used to facilitate posterior rotation of the right 8th rib, and thus right rotation of the entire ring (Figure 1b), as the legs and pelvis are taken to the left. Prior to bringing the pelvis back to neutral, exhalation is used to facilitate greater activation of the right TrA (Hodges & Gandevia 2000).

UI is a powerful biofeedback tool (Tsao & Hodges 2007) and was used to teach Tara more about the dys-synergies in her abdominal wall and to understand (left brain) and internalise (right brain) better ways to recruit and use these muscles for her trunk control during rotation loading (running and kayaking). Time was spent empowering her with the education and sensorial experiences she needed to continue to build a different ‘brain map’ for using her abdomen (Tsao et al 2010). We talked about how this was not about ‘exercise’ and ‘strength’, but rather about motor control and muscle patterning. Better strategies needed to be ‘re-built’ first and then she could progress to strengthening exercises. I introduced her to the science of neuroplasticity and directed her to articles and related books on the topic for her own personal and professional learning (Boudreau et al 2010, Doidge 2007, Siegel 2010, Snodgrass et al 2014, Tsao et al 2010). She was encouraged to release her right EO and engage her right TrA frequently over the next seven to ten days, and then to integrate a pre-contraction of the deep abdominals (both TrAs) with the rest of her core muscles whenever she lifted/loaded her trunk. In addition, she was taught to correct the alignment of the 8th thoracic ring in sitting and encouraged to practice maintaining this correction (initially manually and then with imagery) as she rotated her thorax to the right. Once the 8th thoracic ring mobility and control was restored in this task, I felt she would be able to increase her loads and move towards integrating this new strategy into her running and kayaking.

This session was booked as a consultation only since Tara lived a considerable distance from my clinic and was initially interested in just one session for an opinion on appropriate exercises for her ‘core’ and advice on surgery. Consequently, we did not have a follow-up session for one month.

Reasoning Question

Even simple home exercises are sometimes challenging for patients to learn. How do you facilitate this with more complex exercises such as those you taught Tara?

Answer to Reasoning Question

Awareness, focused attention, training tasks that have meaning, and massed practice of high quality movements to normalize the sensory input and thus change the motor output are all requirements for neuroplastic changes to occur in movement behaviour. This can be achieved very quickly given the right clinical environment and sufficient time with a motivated patient. If you are able to change a person’s ‘experience’ of their body in a positive way, empower them to take responsibility for the next steps of their ‘brain training’ and use tools such as video recording their movement practice on their mobile phone, then change can occur quickly and with few appointments. The paradigm shift here is for clinicians to stop taking full responsibility for ‘fixing their patients’ and for patients to understand that clinicians can merely ‘illuminate a path to change’. It is up to them to do the work. Tara was highly motivated and understood and accepted the work she needed to do over the next month. She left this first appointment with videos on her mobile phone of exactly what and how much she needed to do. She felt confident that she could follow through with the program and knew that she could contact me via email with any questions over the next month.

Follow-up – One Month Later

Subjective Report

Tara noticed progressive improvement in her functional abilities and significant reduction in both her low thorax and upper lumbar pain with repetitive loading tasks since learning to ‘re-organize the use’ of her abdominal wall and regain control of her 8th thoracic ring. She reported the local tenderness at the spinous processes of T8-T10 persisted, however the intensity and frequency of the ‘achiness and fatigue’ was less and more activity (e.g. longer running time) was required to provoke the symptoms. She was not kayaking yet. She was pleasantly surprised at the change in her abdominal profile (Figure 7a,b).

Physical Examination

Standing Posture

Physical examination of her standing posture revealed better thoracopelvic alignment; her pelvis was in neutral alignment, as were her 8th and 9th thoracic rings. Since minimal attention had been directed to her 3rd and 4th thoracic rings there was still some upper thorax asymmetry, however they were not interfering with her lifting or running ability.

Supine Curl-up Task

Clinically, both at rest and during her automatic supine curl-up task the infrasternal angle was more symmetric (Figure 8a,b), suggesting that the resting tone of the left and right EO and IO was more balanced.

Without ‘thinking of’ pre-contracting the TrAs, doming of the abdomen was still present and the LA still felt somewhat lax (Figure 9a) (i.e. was easily distorted with finger pressure). Pre-contracting the TrAs significantly increased the palpable tension in the LA and this was improved further by stabilising the 8th thoracic ring (Figure 9b), suggesting further control was still required during this task.

No manual interventions for release of the EO were given during this treatment session. We focused on more movement training and control of the 8th thoracic ring for achieving her goal of being able to run and kayak with ease and without exacerbation of back pain. Both tasks require controlled thoracopelvic rotation, while running also requires alternate flexion and extension of the hips.

Many postures/poses in yoga are useful for rehabilitation of fundamental and functional movements. Parivrtta anjaneyasana, the Sanskrit name for lunge with twist (Figure 10a,b,c), is a useful pose, or task, for runners. To perform this pose well, thoraco-lumbo-pelvic mobility and control (both segmental and regional) is needed, as well as lower extremity mobility and control that far exceeds that required for running. Tara was taught how to do this exercise or pose with optimal alignment, biomechanics and control from the 4th thoracic ring to her foot, with an emphasis on her 8th thoracic ring alignment, mobility and control when rotating to the right and the 4th thoracic ring when rotating to the left. To do this well, she needed cues/images to relax/release the right EO, correct/align/control the 8th thoracic ring, activate the right (and left) TrA, rotate her thoracic rings congruently to the right, flex the right hip and knee and extend the left while maintaining optimal foot control and contact with the floor – no small task! Multiple myofascial slings (Vleeming et al 1995), chains or trains (Meyers 2001) require collaboration to do this well, and with repetition (massed practice) and focused attention (awareness) a better strategy for thoraco-lumbar-pelvic rotation mobility and control can be trained.

Considerable time was spent in this second session ensuring Tara understood the movement practice and she continued to work on the release, alignment and control of her thoracic rings in relationship to her pelvis and hips independently. She was satisfied that she would be able to progress her training on her own and she was advised to return for follow-up advice as necessary.

Reasoning Question

Recognising you probably use a range of cues and images to facilitate a patient’s understanding, awareness and efficacy for controlling the multiple components you highlight in the yoga lunge with twist exercise, would you provide your tips on cues and images you find most effective?

Answer to Reasoning Question

This is difficult to answer because ‘cues’ are often based on an individual’s past experiences and sometimes their culture or geography; they are highly individual. For release, words that suggest letting go or melting, lengthening, creating space between the bones of the compressed joint/region, or expanding seem to work best. For connecting integrated myofascial units, words that link them together are effective such as: ‘imagine a guy wire between your left and right ASISs and find a way to connect them together’ or ‘gently lift the arch of your foot and continue that gentle lift up the inside of your leg picking up your pelvic floor, keep that and now expand the lift up through your thorax letting your ribs separate and on your next exhaled breath see if you can add a small twist between your chest and pelvis’. The nervous system appears to respond best to images and sensorial cues as opposed to ‘being told what to do’, and sometimes when the person does exactly what you feel is correct, you merely need to ask them what they are thinking about as they are doing this. This way your inventory of cues will grow; let your patients teach you how to do this. Eric Franklin’s book Dynamic Alignment Through Imagery (1996) motivated me to try imagery for my patients with pelvic pain years ago (Lee D 2001). Imagery and visualization is used extensively in sport and dance for facilitating better strategies for movement.

Clinical Reasoning Commentary

Contextualised use of metaphors as suggested here is well supported by their ability to activate sensory-motor systems enhancing learning. The craft of teaching is again evident in this answer. Working backwards from correct patterns of controlled posture and movement to the patient’s particular thoughts can assist patient’s recognition of unconsciously used metaphors, while also building our own ‘inventory of cues’ for use with future patients.

Seven Months Later

I contacted Tara to ask how she was doing. Here is her emailed reply:

I am feeling really good about it all 🙂 I am able to participate in all desired sports/activities, though not yet to the same intensity as pre-pregnancy, but I am still steadily improving. [She also stated she was completely free from all pain in the thoracolumbar and mid-thoracic regions.]

Having said that I have been meaning to email you and ask your clinical opinion on what you would consider a realistic expectation of what my stomach can endure with respect to another pregnancy.

We are considering trying for baby #2 very soon and my only concern is how my stomach will tolerate the pregnancy. I know there are numerous variables and no concrete answers, but in your experience have you seen women with a situation similar to mine come out of a second or third pregnancy with minimal progression of their diastasis or should I be mentally prepared for things to likely be worse?

No matter what the answer, it isn’t going to sway my decision to have a second baby :), but I would like to be realistic about what I am getting myself into!

There is no literature or research to provide Tara with an evidence-informed answer. No studies have yet determined what causes the LA to widen excessively in some women during pregnancy. For Tara, according to Beer et al (2009) her IRD just above the umbilicus (her widest point) was only slightly wider (2.55 cm) than what is considered to be ‘normal’ (2.2cm) (at rest). In my opinion, her minor DRA was likely caused by the dys-synergy of abdominal recruitment pre-existing her first pregnancy and hopefully now that her abdominal musculature was more balanced and her 8th thoracic ring control was improving, her abdomen would tolerate the required expansion necessary for her second pregnancy without any long-term damage.

Reasoning Question

It sounds like your prognosis for Tara was positive, both with respect to her pain as well as the ability of her LA to withstand a second pregnancy. Given Tara had ‘questions regarding the pros and cons of a surgical repair of her abdominal wall’ at her first appointment, please discuss your views on the indications for surgery.

Answer to Reasoning Question

There are many subgroups of women with DRA and treatment is highly individual (Lee & Hodges (submitted)). However, in general, it can be stated that there are two kinds of DRA: those who we can help with physiotherapy (using a multi-modal approach to restore optimal function of the abdominal wall) and those who require surgery (recti plication [approximate the recti] and abdominoplasty] repair the skin]) and then physiotherapy (often with physiotherapy before surgery as well). When should we refer women with DRA for consideration for a surgical repair? While research is lacking to definitively answer this question, within my clinic we have now collectively treated over 100 women with this condition and our combined clinical expertise suggests that surgery should be recommended if the individual:

1. Shows poor control of the joints of the thorax, lumbar spine and/or pelvis during multiple functional tasks.

2. Demonstrates optimal neuromuscular function of all muscles of the abdominal canister (assessed both clinically and via UI) but little ability for this apparent optimal strategy to control motion of the relevant joint(s).

3. Cannot generate tension of the LA during a contraction of the left and right TrAs or during a supine curl-up task.

It appears that function can be restored without closure, or narrowing, of the IRD in some women with DRA, such as Tara. This finding challenges the commonly held belief that closing the DRA is a pre-requisite for restoration of function. The ability to generate tension in the LA with an optimal abdominal recruitment strategy instead appears to be the factor differentiating those who require a surgical repair from those who do not.Figure 11a,b illustrates the standing abdominal profile of a woman with what was determined to be a surgical DRA. Clinical examination revealed that she was able to co-activate the muscles of her abdominal canister and yet this optimal strategy was not able to provide control to her low thorax and upper lumbar spine.

Both doming and invagination of the LA (Figure 12a,b) can occur during a supine curl-up task; it depends on the resultant intra-abdominal pressure and the recruitment strategy of the various abdominal muscles and the diaphragm.What is consistent in the surgical DRA group is that they are unable to generate tension of the LA in spite of an optimal abdominal wall recruitment strategy, and this lack of tension can be both felt (palpation for tension in the midline during a supine curl-up task) and seen via UI (high distortion of the LA and low echogenicity). We have now followed 12 women through surgery to repair the abdominal wall and all have experienced an improvement in both appearance and level of functional ability (Figure 13a,b).

Clinical Reasoning Commentary

As presented in Chapter 1, the ‘Hypothesis Category’ Prognosis refers to the therapist’s judgment regarding their ability to help their patient and an estimate of how long this will take. Broadly speaking, a patient’s prognosis is determined by the nature and extent of the patient’s problem(s) and their ability and willingness to make the necessary changes (e.g. lifestyle, psychosocial contributing factors, physical contributing factors) to facilitate recovery or an improved quality of life within a permanent disability. Little research is devoted to identifying predictors for the effects of specific treatments for particular musculoskeletal conditions, although some clinical prediction rules are a relatively recent move in this direction (see Chapter x). However, before being subjected to research, prognostic criteria for successful therapeutic management (e.g. neuromuscular retraining for DRA) must first be clinically recognised and clinically ‘tested’, as described in this case. To assist clinical reasoning regarding prognosis we recommend explicitly identifying both positive and negative prognostic indicators throughout the full clinical presentation. This lessens the likelihood of an error of over-focusing on one or two key positive or negative features and facilitates a more considered decision.

Skills Demonstration

Case Study Author

Clinical Mentorship in the Integrated Systems Model

Join Diane, and her team of highly skilled assistants, on this mentorship journey and immerse yourself in a series of education opportunities that will improve your clinical efficacy for treating the whole person using the updated Integrated Systems Model.

We will come together for 3 sessions of 4 (4.5) days over a period of 6-8 months with lots of practical/clinical time to focus on acquiring the skills and clinical reasoning to put the ISM model into practice. Hours of online lecture and reading material and 12 hours of in-person lecture are...

More Info